The harmony of tinkering and clicking sounds greets sophomore and Robotics club member Abigail Brown as she enters the engineering classroom. Yet instead, she’s met with the overwhelming lack of girls in the club.

“You honestly feel so stupid,” Brown said. “And they don’t do it on purpose. Basically all the student leaders and everybody in there are men. It sucks because you’re supposed to look up and be like, ‘Yay, these are the people who are leading me’ and instead they are all a bunch of old white men.”

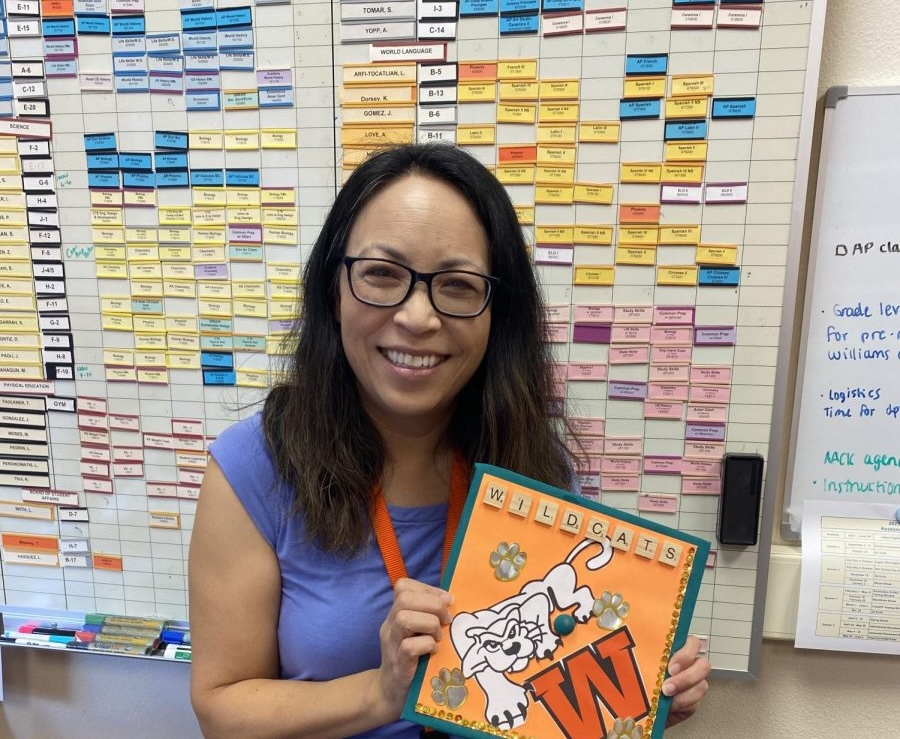

In other words, girls experience imposter syndrome: feeling like a fraud among skilled individuals. At Woodside, this common narrative can be seen in the lack of female students in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) electives such as Computer Science, Animation, Engineering, and Audio/Music Production. Currently, females make up 21.6% of these classes, a notable issue for many teachers. So, what causes this skewed gender gap in STEM classes?

Reasons for Gender Gap:

When girls reach high school, often interest and motivation to enroll in STEM classes decreases. Researchers indicate that in middle school, 74% of girls demonstrate having interests in STEM subjects. This number drops as soon as girls reach the high school level, a result of societal pressures.

“[During the transition from] middle school to high school, you start to be like, ‘Oh, are there other people around?’” engineering and physics teacher Philip Hopkins said. “You start to look around the room and [wonder], ‘are there other women in here?’ [Then you start to think,] ‘Oh, there aren’t as many [women], maybe I shouldn’t be here.’ That unfortunately leads some people to leave the fields.”

For Hopkins, female interest in STEM classes is often dictated by a growing maturity and greater awareness of what others think of them. When girls reach high school, they become more conscious of societal perceptions towards them, often in the form of targeted advertisement. Gender specific advertisements are used by many brands and companies that reinforce gender stereotypes through portraying a product that’s supposed to appeal to a certain gender. However, usually these advertisements target females with a survey by Spiceworks sharing that 57% of people surveyed believe advertisements target women.

“[Girls] start to reflect, even if it’s not consciously, [that] advertisements are more targeted to one demographic versus the other,” Hopkins said. “I think that starts to reinforce some of these unfortunate trends that we’re seeing.”

Peer pressure and feeling isolated in these male-dominated classes can create an uncomfortable environment for many girls, such as for freshman Danica Chandler.

“It might be awkward because there are a lot of guys in our class,” Chandler said. “None of the girls except for three in the front are next to each other. So all of us are just next to guys, and that can be really uncomfortable.”

This uncomfortable feeling is perpetuated with continuously pairing only girls together instead of with boys. Girls find this to be a reflection of their inability to work with males.

“One thing I do notice is they don’t tend to pair guys with girls,” Chandler said. “So it’s a lot of girls working with girls, [and] guys working with guys. I think that’s interesting. Why are there no co-ed partners?”

These reasons lead to girls making up one third of audio/music production and computer science classes. Engineering classes show a similar trend with a limited number of female students.

“In one of my engineering classes I have 10% [female students],” Hopkins said. “I think it’s three girls to 35 boys. So not even 10% [girls].”

Many girls at Woodside often don’t know about the STEM electives available to them, and are disappointed after realizing what classes they could have taken.

“I feel like they didn’t really guide us well to know what classes we were able to take this year,” freshman Luna Chavez said. “So it was like I was really confused at the beginning of the year, and now I’m finding out that I have more opportunities [for] class [choices].”

Yet when it comes to Advanced Placement (AP) STEM classes, girls jump at the chance to join these courses, making up the majority of these subjects. In the AP Biology class, for example, there are 63 females to 31 males. Other AP classes follow suit with an equal distribution of gender.

“The courses that are traditionally in a pathway like the statistics class or the biology class, you’ll probably see more females than males in those classes,” head counselor Francisco Negri said. “But the elective classes are where you’re going to see the giant skew the other way.”

This skew in the elective classes is often confusing for the girls in these classes who have gained valuable experiences and are grateful for taking these courses.

“I don’t get why more girls don’t want to do it,” Chandler said. “I mean, we get to make songs based on artists we personally like and get to have our stuff [put] out there. It’s awesome and fun for us.”

The real answer to the pushback against STEM classes may not have started in high school, but at a younger age with the way females are raised.

Gender Stereotypes:

Girls find that they are constantly pushed towards more creative subjects rather than STEM classes, which are considered more for males.

“I think there is definitely more of a push on girls to do art and things like that,” freshman Katherine Jasinskyj said. “I think when it comes to engineering, computer science, or mathematics, it’s definitely [geared] towards men. That’s because a lot of people used to think that men were the only ones able to do mathematics and stuff like that.”

This push towards creative courses marks another distinct gender gap, with males conversely making up a smaller percentage of art classes. The College Board noted this in 2019 after reporting males making up 23 percent of the 65,000 AP Studio Art portfolios submitted. At Woodside, this trend is reflected in many art electives, such as drama, where boys make up a smaller portion of the class.

“I think the culture here just made it seem unrespectable [for men to be in drama],” sophomore Owen Weibell said. “[Boys are] scared to do the things [boys] want to do.”

As a drama teacher at Woodside for many years, Bary Woodruff finds that many of his female students demonstrate a greater maturity compared to males, increasing their willingness to try new things.

“Girls are more willing to do things [and take] risks at this age,” Woodruff said. “A lot of guys just want to be cool.”

Being a former student at Woodside who was a baseball player, theater kid, and champion ballroom dancer, Woodruff has had firsthand experience when it comes to guys stereotyping drama.

“I used to get teased [when I was] on the [pitching] mound,” Woodruff said. “[They’d say,] ‘Hey, where’s you tutu?’… So you get made fun of and stuff. You just have to be strong enough to say, ‘Okay, this is what I want to do, [and] I don’t care what [others are] saying.’”

Despite male stereotypes surrounding drama and the need to ‘be cool’, many plays and musicals aren’t written for more female roles. Often females are forced to play male roles in order to be a part of drama productions.

“We can do so many more shows if we have guys because so many of the shows are written for guys,” Woodruff said. “That’s been the complaint of [girls] for a long time. Where are the great parts for the women? A lot of my girls are used to playing in boy parts. They get to high school, and it’s the first time they get to play a girl.”

Most STEM industries aren’t welcoming of females as they often prioritize the interests and successes of males over women. This is apparent in the production side of the music industry. Despite organizations like the Women’s Audio Mission in San Francisco, Audio/Music Production teacher Raphael Kauffmann finds that women in the industry are still scarce.

“[There is a certain] shroud on the STEM classes that makes those careers or those interests more geared towards males, but it’s so nonsensical,” Kauffmann said. “It is reflective of the industry as well. Music production has traditionally been male dominated, which is not a good thing. We’re having to reflect on why that is, and what we can do to change it.”

Solutions to increasing females in STEM:

To increase female students in STEM classes at Woodside, teachers are creating groups aimed to discover the basis of this issue, and what can be done to increase girls in these classes.

“We have a collaboration group called Computer Science (CS) for all,” Algebra I and Computer Science teacher Swati Tomar said. “I started [this club because] I wanted to see how we can improve the number of girls in computer science courses or in any STEM class.”

Some activities this group has done to advertise computer science classes is inviting female students to lunch-ins that explain what is taught in these classes.

“I was invited to go to this meeting about computer science, and they talked about how they wanted more girls to join their classes,” Chavez said. “But I feel they don’t advertise it well enough. For me, it didn’t really catch my attention.”

Additionally, the engineering courses aim to bring more female guest speakers to highlight career options in STEM for female students.

“We’ve had Dr. Lauren Abrams and Mr. Filerman’s wife who came in and talked about her work as an engineer at Lawrence Livermore National Lab,” Hopkins said. “Earlier this week, Ana Ruiz came in and [she talked] to one of my engineering classes about being a pilot [and] being a woman in aviation.”

In the end, finding ways to grow a female community in the STEM program is an uphill battle that Woodside continues to climb with each passing day.

“We just have to keep on working even harder to try to make sure that students feel safe and comfortable in these spaces that historically have not treated these groups well,” Hopkins said.