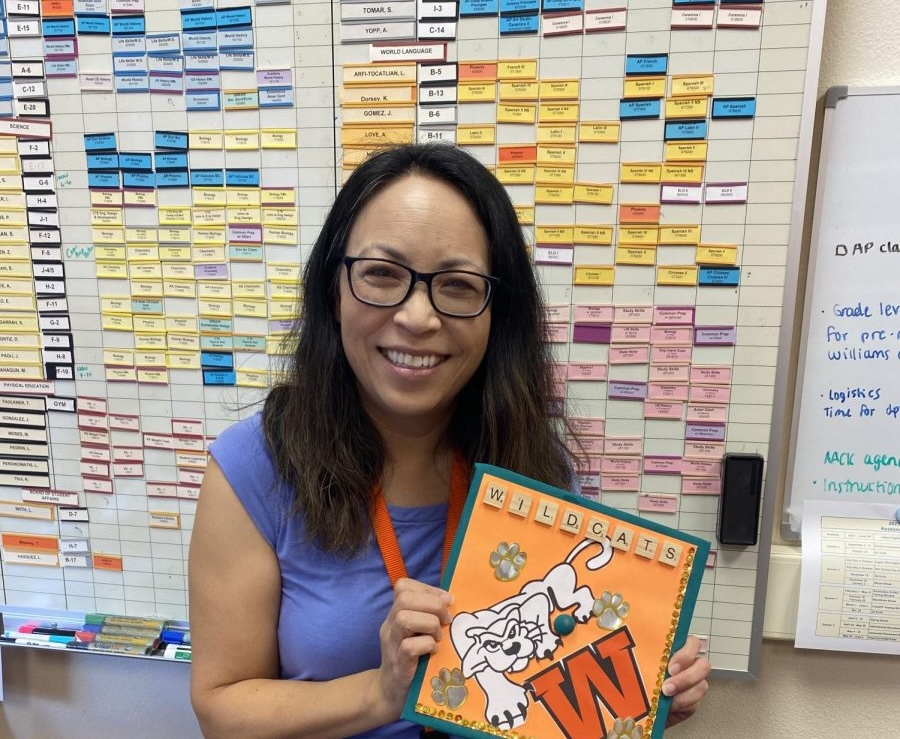

Teaching AP Environmental Science, chemistry, and leading the Green Academy is no small task, but it helps if you have some experience.

Luckily for Ann Akey, that’s exactly what she has.

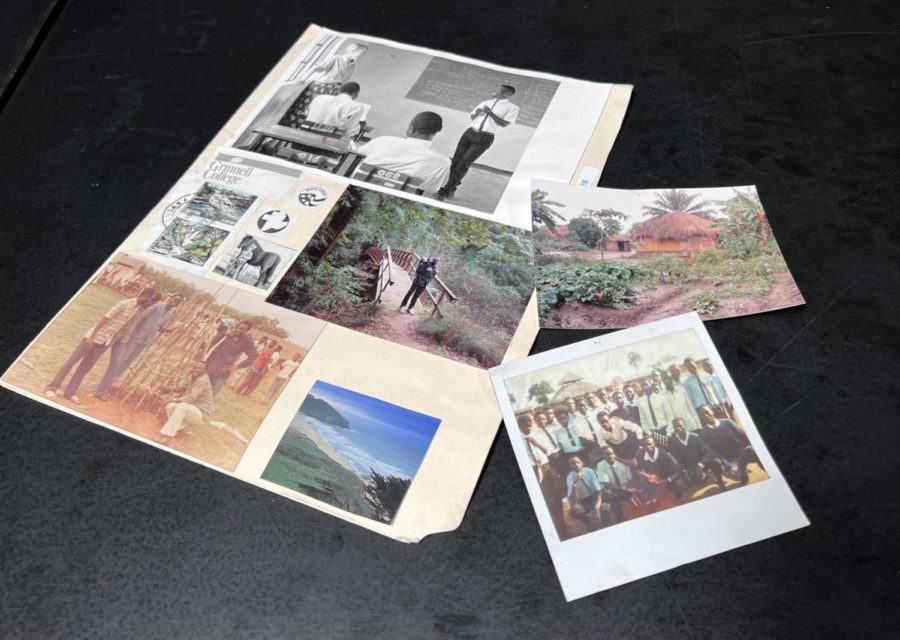

Ever since high school, Akey has traveled around the world volunteering and teaching kids in places as far off as Zambia and Paraguay. In between, she’s studied in the cornfields of Iowa, tracked pelicans in Costa Rican trees, and even tutored students in inner-city Sacramento for a year.

Growing up in Palo Alto and attending Gunn high school, Akey had her first taste of life outside the U.S. traveling to Paraguay her junior year. At the time, the South American country was in the midst of a worsening measles outbreak, with around 220,000 cases reported annually and a skyrocketing death rate. Akey – through the Spanish immersion program Amigos – helped to administer door-to-door vaccinations for the disease, as well as those for diphtheria and tetanus. The experience helped her see the world in a new light.

“I think it widened my understanding of the so-called developing world,” Akey said. “ I was amazed to see that many people I met in Paraguay my first summer, were actually a lot happier than the people I knew around me in Northern California, even though they had a lot less.”

As a result, the experience gave Akey the motivation to travel more and gain new perspectives

“I also got a bit of a travel bug, I guess, [and] a desire to see other cultures and to visit places,” Akey added.

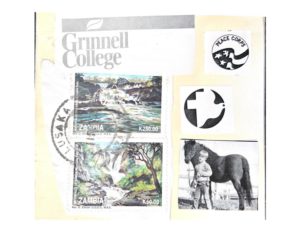

College

Akey soon went to Grinnell College in Iowa to earn a degree in Biology. While Grinnell was a tiny school far from home, Akey was drawn to its small size and reputation as a top liberal arts school. It was her junior year there that led to her second voyage—one to study the declining Brown Pelican in Costa Rica

“I got to this wonderful tropical island up in the far north of the country on a bay between Nicaragua and Costa Rica,” Akey described. “Another woman and I would get a fisherman to take us out to the island every week for a few days, spend most of the week watching birds, and then come back and take a day or two in town resting and restock[ing] stuff.”

According to Akey, there was always something going on with the large-billed seabirds.

“To be honest, just watching the pelicans [out foraging] come back to the island at nightfall… was fascinating,” she remembered. “I was mostly watching the chicks, and that’s brutal because, as you know, they may have three or so chicks… They [soon] fight each other, and often one pushes the other out of the nest. There’s this competitive thing going on.”

While the research eventually helped poor survivorship for Brown Pelicans and Magnificent Frigatebirds due to DDT use that year, Akey remembers the experience in particular for the awkward politics involved with that trip – a theme that would later pop up on some of her other trips.

“The United States at that point was having some political issues with the Sandinistas in Nicaragua,” Akey explained. “And all of a sudden, here’s this American sitting up in a tree looking out over Nicaragua, with binoculars no less. Now there’s helicopters flying around, and that’s when I stopped my research for a couple of weeks. It was like I did not mean to get into an international issue. As a 20 year old woman, I wouldn’t have thought … [they had suspicions of me], but they were getting more and more interested in what I was doing up in a tree with binoculars; and birding just ended up getting confused with spying.”

She notes that, as a result of the survivorship and other complexities, the Costa Rican government ended up shutting down access to the island after that year, ending her time doing research in that area.

Benin

Just out of college, Akey didn’t originally aim to become a teacher

“[I] had no intention of ever doing that. I thought anyone who wanted to teach was absolutely crazy,” she confessed.

Yet, after her stint at Grinnell, she found the opportunity to go to Benin as a volunteer for the United States Peace Corps. It was there that they asked her to teach at a school in the West African country.

“They suggested it was a possibility, and I thought, ‘Okay, for two years,’” Akey remembered. “I’ve had some good teachers, I can give back just two years.’

Due to Benin’s ties as a former French colony, Akey ended up teaching all her classes in French, which she had dropped in high school for the “more practical” Spanish. Once she settled in and began enjoying her classes, she found that teaching was something she enjoyed.

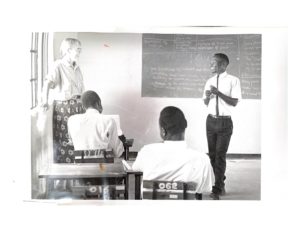

“My classes were 55 to 60 students and without running water and electricity,” Akey recounted. “[It was] a little different teaching [and] just fascinating [with] fun and wonderful students [who were all] very highly motivated [and] very much valued their education… I found that I didn’t mind teaching after all and enjoyed the young people with whom I was working.”

On one trip, in particular, Akey remembers a scare she had when a student came up to her with a dead snake in his hands.

“I remember my field trips were all walking field trips for the school…, [and] when we were out in a forested area, one student comes up to me with a five-foot long, bright green snake hanging over a stick,” Akey recalled. “I liked snakes when I grew up here, but living in places where there are many, many poisonous snakes you learn to kind of [avoid them]. So, that cost me a couple of gray hairs, but it was laughable.”

Along with interesting creatures just outside school grounds, there were other differences Akey noted between classes in the U.S. and those in Benin.

“Number one, there are no books, so you, [the teacher], are the textbook … The classes are also big and the students are all wearing uniforms,” Akey said. “Some of my high school students were older than I was because if you don’t pass a grade, you repeat it – it’s very selective. There are no automatic advancements and grades, and oftentimes, half the class will fail.”

Another thing she noticed was the lack of gender diversity in the classrooms

“By the time you get to the upper levels of high school, there’s hardly any female students,” Akey pointed out. “The fact is, for most of the time I was there, I was the only female teacher at my school too. Not only was I the only non-African teacher, I was the only female teacher.”

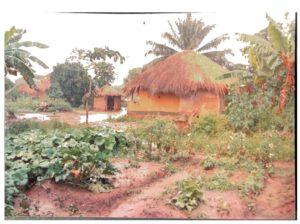

One thing everyone shared, however, was the nonstop heat that often broke up classes. Akey remembers “midday heat naps” were a common thing to do during school in Benin

“We’d get to school at eight and it would already be so hot, that sweat would be dripping down on you. And these buildings, they didn’t have ceilings – they only had those sheet metal roofs – so it was crazy hot. By noon, everyone goes home, and basically, you treat for heat exhaustion. You drink a lot of water, and you take a cold shower – you only have cold water anyhow – and you lie down… Then, three hours later you go back to school and finish the day.”

A 2010 study on heat in nearby Cameroon noted that local students were more likely to show fatigue and suffer from headaches and other problems on days when classrooms got excessively hot, correlating with an overall drop in performance during the hottest hours of the day.

“That siesta thing is really a necessity when you don’t have air conditioning, you don’t have electricity, or … don’t have fans. It’s just excessively hot,” Akey said.

Weather, in general, often affected how well Akey could teach her classes, especially when the CMGE Pobe school she taught at was hit by rainstorms.

“The storms would be so incredibly intense that, again, those metal roofs – when it started raining hard – just kind of gave up no classroom management because no one could hear anything. Students loved it because they just realize that teachers have no control of the class at this point, because they can’t be heard, so they just start doing whatever they want. It was just kind of just a lark,” she laughed.

Overall, Akey says taking that first Peace Corp work in Benin helped her gain a new outlook on the US

“In retrospect, I learned a lot about the United States and myself through viewing the United States from afar and from not being there surrounded by it. I could understand a bit [the concept of] my culture versus my personal beliefs and values and I could separate those a bit more easily. So that was in so many ways enlightening.”

Zambia

After Benin, Akey spent three years earning her master’s degree in plant ecology at Iowa State University in Ames, Iowa. It was there that she met her future husband.

“We were both asked to help another graduate student with her research,” Akey remembered. “ So, I remember biking up to Bessie Hall – the botany building at Iowa State – and there’s this guy sitting by the bike racks [and] turns out he’s also been roped into helping her. And that’s how I met him.”

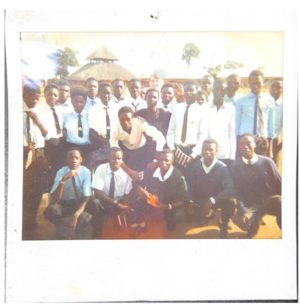

Together, the two moved to Zambia, where Akey again taught high school while her husband worked for the local Mennonite Central Committee. While Akey remembers it being similar to her work in Benin, there were some notable differences.

“I mean, it was very different [in general] and a very different colonial history – Zambia was a British colony, Benin was a French colony. I was able to teach in English [in Zambia] and I studied Cibemba (the local language in Zambia) for a while, but it’s a very different type of infrastructure.”

Yet, Akey notes that, much like in Benin, students in Zambia were always ready to learn

“I had very enthusiastic students in school. In places where not everyone goes through secondary education, the people who do [get through] really prize it. It’s really a very different feeling than a place where you have to be in school whether or not you want to. When it’s a choice and not always easy, I think there is a different sort of feeling.”

For many teachers, jokes are usually part of the routine to get students engaged and keep classes exciting, even here at Woodside. Yet, as Akey remembers, getting some of those across was difficult in Zambia despite it being the same language.

“What amazed me is, I would try to say something like a joke, and students would just blankly look at me,” Akey remembered. “Then I’d be talking seriously, and students would break out laughing. That’s just what happened frequently. If I say something here, like, ‘back in the age of the dinosaurs when I was your age,’ you would know not to take something like that seriously. But [not there]. The cultural clues and the expectations are so very different, and it’s wonderful fun as one learns and becomes more comfortable with the culture in the language, but it can be a lot of confusion.”

Despite all the optimism and laughs, however, Akey’s time teaching in Zambia was notably overshadowed by the ongoing AIDS epidemic, which again opened her eyes to the problems that many developing countries faced.

“It’s frustrating that – then and [even] today – resources are low, and people are dying of preventable diseases,” she recounted. “I was there during the height of the AIDS epidemic… [where there were] a lot of people infected – but before there were effective retroviral drugs. So lot of my colleagues got sick, [and] people I worked with closely have since died, [some] within a year or two of me leaving.”

After Zambia, Akey took one more teaching gig before returning to the Bay— a year-long stint at a high school in North Sacramento for which she was “sorely unprepared for.”

“There were … fights in my classroom; there was all sorts of gang stuff,” she mentioned. “It was a tough school. A lot of kids had parents in prison.”

Despite the hardships, she again took home a valuable lesson from the experience

“I think it woke me up to too many things I had to get a background in [for] both approaches to teaching and learning more about my students’ backgrounds,” Akey recalled.

Finally, in 1999, she was hired at Woodside High School to be their new Environmental Sciences teacher.

Traveling Today

While Akey has ended her worldwide teaching tour for now, she still enjoys the occasional travel. Yet, on a trip back to Costa Rica around a decade ago, she lamented how much the country had changed from her Pelican days.

“It had been 23 years since the time I was there previously— and my goodness, it was so much less unique… [and] so much more like the United States,” Akey said. “My kids went down with me, [and] we went to a language school where they watched ‘Les Increíbles’ – or The Incredibles. They were watching the same movies, albeit in Spanish, with the host family… [because] you could go rent DVDs now… Off course, [the country] should have changed in 23 years – I get it – but it’s also less unique. It kind of seemed that it had more and more American culture kind of permeating through it, so it’s kind of bittersweet.”

Ever the environmentalist (she still bikes to school most days), Akey does recognize that her past travelings weren’t the best for the planet due to their reliance on long airplane voyages to get to places like Zambia and Paraguay. It is, however, one reason why she shies away from any exotic vacation trips these days.

Well, I’m aware that it’s a [fairly] high carbon footprint,” Akey admitted. “But unlike people who just travel, I haven’t traveled as much as I’ve just gone and lived places for extended periods of time … [Now though], in terms of ‘oh, now, it’d be nice to go spend two weeks someplace,’ I’m a little bit more hesitant.”

Ultimately, from the mornings watching Pelicans on a Costa Rican island to beating the midday heat in the Benin desert, Akey says she is grateful for her years teaching and traveling around the globe and the memories that came with them.

“I loved it. I wouldn’t trade it for the world.”