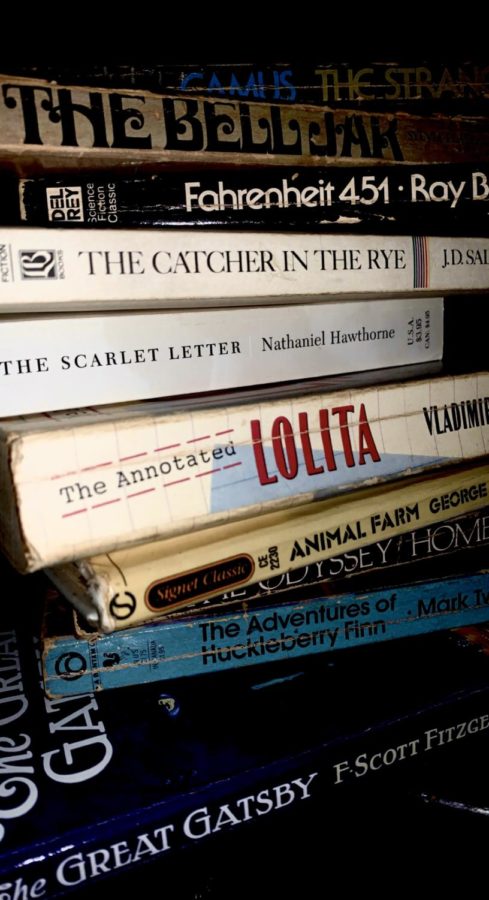

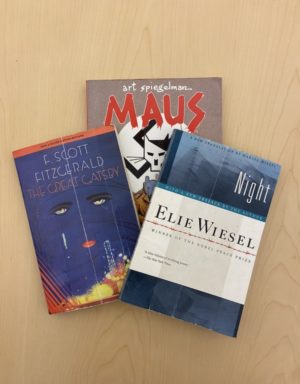

Controversy surrounding the censorship of books like “Catcher in the Rye” by J.D Salinger, “Maus” by Art Spiegelman, and “Huckleberry Finn” by Mark Twain has sparked a national debate as to why certain literary pieces continue being implemented in high school and middle school curriculums despite complaints from different audiences.

Explicit topics and language are the most common reasons for the censorship of literary works, and parents tend to get involved when they feel their children are being taught inappropriate material. Classics like “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald and various Shakespearean plays have been taught for decades; so the question of whether books should be banned or not is becoming heavily debated.

In January, a school board in Tennessee gained national attention when they banned the teaching of the book “Maus”. A community uproar ensued which added to a national discussion of what should or shouldn’t be taught in the classroom that had been building all year with debates about how to teach race.

The book “Maus” revolves around the narrative of a mouse (maus in German) who is interviewing his grandfather about his experience as a Polish Jew and Holocaust survivor. It is a nonfiction narrative about the author’s personal anecdote told through the eyes of a cartoon mouse and is laid out in a cartoon/graphic novel format.

“In the case of Maus, it’s an important topic, the Holocaust, and it’s a very effective book because a lot of students really liked that graphic novel format,” library media teacher Anne Ken said. “So I think something like that should be allowed. It’s teaching the truth of the topic, but in a way that a lot more students might be interested in that topic.”

The Tennessee school board banned Maus in its eighth-grade arts curriculum due to Maus’s portrayal of female nudity and profanity. English teacher Alexandrina Pretto teaches many controversial books to her advanced sophomores such as “Maus,” “Night” by Elie Wiesel, “Oedipus Rex” by Sophocles, “Kite Runner” by Khaled Hosseini, “Never Let Me Go” by Kazuo Ishiguro, and “Buddha in the Attic” by Julie Otsuka.

“It seemed very misguided on the part of the [Tennessee] school board because the Holocaust is a terrible, factual historical event,” Pretto said. “By banning Maus, you’re simply banning access to information. When you limit access to history and to controversial subject matter, you limit the ability of our young people to understand the world, fight against injustice, and be horrified appropriately at horrific events.”

Shortly after the banning of “Maus,” the author Art Spiegelman spoke with the Tennessee school board. Although he completely disagreed with the school board, he did say that he had intended for the book’s audience to be adults and not students, since it depicted very serious and personal aspects of his life.

“I absolutely think that [Maus] should be taught,” Pretto said. “I disagree with Art Spiegelman. I think it works really well for high school students who are mature and ready for it to be used in conversation around other pieces of work around the Holocaust like we did it.”

“Night” is another classic novel about the Holocaust. It is an intense novel, written from the perspective of a Holocaust survivor, that has been deemed sensitive and controversial for students to read.

“I’ve taught ‘Night’ so many times, and I kind of hate it because it’s the Holocaust: heartbreaking and awful,” Pretto said. “And my family’s Jewish, so I dread [teaching ‘Night’], but it’s so valuable for the students. It’s important, and so I do it anyway.”

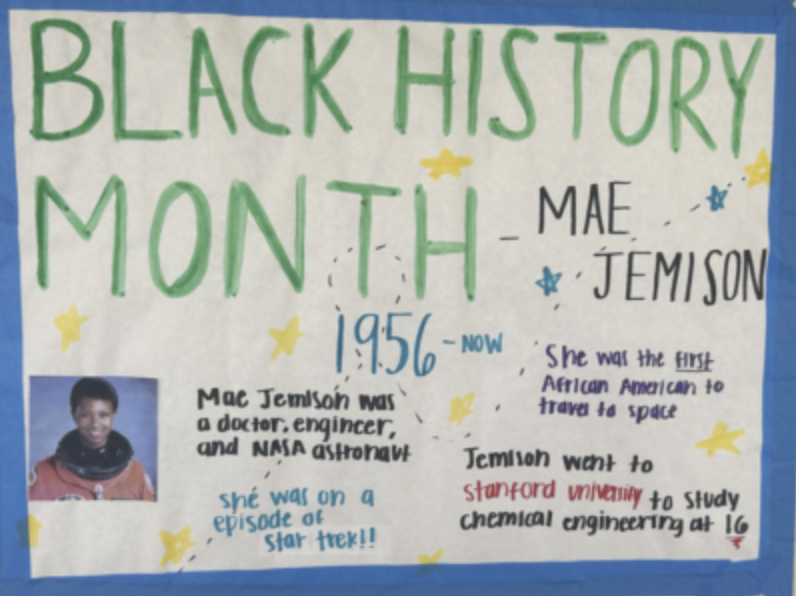

Exposing the gritty truth of topics like the Holocaust and America’s history with slavery is one of the goals when teaching literature. The conversation no longer revolves around if we can ban books, but if we should ban books at all.

“In a literal sense, I think we can ban books, like how “Mein Kampf” by Adolf Hitler is banned in Germany, but then again that is Germany and that seems like a pretty good decision,” English teacher and author of NY Times Bestseller “Wabi Sabi,” Mark Reibstein said. “So I think you can say certain books are inappropriate for certain settings.”

With different classic books stirring up conversation about their place in young students’ curriculum, it calls to question if these books are necessary or important for students to learn about.

“A book can give you access to a life experience that maybe you have never had yourself,” history teacher Patrick McDevitt said. “That’s really important with developing empathy, maybe for people who seem unlike you, in reading about their experiences, maybe see some commonalities or some shared either hopes, dreams, and goals.”

High schoolers can be very insensitive with heavy and serious topics, similar to the ones we read about in class, all in the name of a joke.

“Well for one, they don’t know, and two, they probably do know and they just don’t care,” Bookworms Club president and sophomore Michelle Haro said. “But if kids learn more about [varying sensitive topics], it gives you more understanding of what people went through, and to not be insensitive and make jokes about it.”

Reading books allows readers to live out experiences that are otherwise not so realistic. Creating a more inclusive curriculum allows students to be exposed to more types of literature which can boost student engagement and otherwise improve the educational experience.

“Within trying to make [the curriculum] more inclusive, what happens is when students see themselves represented in some way, shape or form within the text, they authentically engage with that content; engagement is the ticket to academic success,” AS English I teacher Jascha Dolan said.

Although books give unique perspectives, those perspectives can be seen as problematic by others.

“If you have something that’s controversial, I think reading a book in class can be a window for a discussion,” McDevitt said. “If you don’t say anything, then you’re normalizing that thought process or that type of thinking which can be really detrimental to students who are looking to school as an authority type of figure and an intellectual guide.”

In California, individual English teachers can decide what books they want to teach their students as long as they are approved by the district board of trustees and cover the CA standards. Dolan explores a teaching method in which students are given a lot of freedom to choose what they read and dissect.

“One of the things that I’m exploring and that I continue to explore is student choice, and figuring out how I can allow my students to pick the right books, but still practice whatever literary skills they are trying to develop,” Dolan said.

Once teachers’ books are approved, it’s up to the teacher to decide how they want to present and teach the material to students.

“I don’t use the curriculum to achieve an agenda with my students,” Pretto said. “We use [books] to engage with challenging subject matter and as a jumping-off point for critical thinking. The students are young adults who are and will be facing challenges in their lives. Being able to engage with the subject matter in safe spaces in my classroom and with guided discussion and guided consideration, I think … it’s valuable.”

Teachers have their own opinions and thought processes, but they also have a responsibility to their students to present unbiased and factual information.

“It’s important to provide books with alternate opinions,” McDevitt said. “Students can more accurately weigh both sides of an issue and then decide for themselves where they stand. But I think giving just one point of view or taking away one point of view is much more harmful.”

Opening up the English curriculum in the American education system could prove beneficial to students, and teachers like Reibstein are starting to recognize this and try to make a change.

For about 30 years, Reibstein taught “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.” Huck Finn has raised one of America’s greatest controversies surrounding a literary piece because of author Mark Twain’s use of the N-word and depiction of black people.

A combination of the controversy surrounding the novel and a desire to create a more diverse curriculum led Reibstein to stop implementing the novel in his current curriculum.

“I would never have taught [Huckleberry Finn] if I thought it was predominantly racist,” Reibstein said. “I don’t think racist books should be taught.”

Left-wing influence plays a role in the curriculum Reibstein has taught because he teaches at Woodside High School, a school in the Bay Area known for being a relatively progressive region.

“In the book ‘Huck Finn; the N-word comes up quite a bit because it depicts a time period and it depicts a lot of ignorant people who use that term,” Reibstein said. “One of the reasons it got banned in left-wing areas is because [of] the use of [the N-word].”

Sensitivity levels have increased nationwide, whether it be by region, political party, or any other classification. These high-sensitivity levels have increased over the years and phrases that were once used nonchalantly, are now essentially forbidden.

“The bottom line is, Mark Twain [was] a white man,” Reibstein said. “Maybe we just can’t read a book where a white man uses the N-word. Lenny Bruce can’t say it in a movie. It’s just that’s where we’re at.”

Reibstein brings up the point that if a person can’t quote someone using an offensive word, even with a justified purpose, then we can not move forward as a society. Understanding the difference between usage and purpose is where the problem truly is.

“Doesn’t matter if you’re quoting [someone using offensive language] or whatever, and I don’t think this is actually a good thing,” Reibstein said. “What I’m hoping students will realize is it’s not the word; it’s how it’s portrayed.”

Despite Huckleberry Finn’s cultural relevance and significance, Twain is still a white man using an offensive slur. This is what has sparked controversy about the literary piece.

“You know, that is why I decided I can’t teach Huck Finn anymore; there’s a lot of great stuff in [Huck Finn] but it’s a white man who, no matter how he’s using [the N-word], he can’t use it,” Reibstein said.

Weighing whether to teach a traditional book that teaches important thematic themes portrayed by a white man or approaching social issues through new books by new authors is difficult for teachers, but important.

“I’ve seen, over the years, that our curriculum [has] opened more,” Reibstein said. “I’ve done it in my class and I’ve actually very deliberately kind of tried to go 50/50 and really break down the number of dead white males and really bring other voices in, but it’s really a balancing act.”

Finding stability between balancing the teaching of classics versus new, progressive literature is also tricky due to the pre-existing cultural significance of classic literature.

“There’s going to be cultural references to [classics],” Reibstein said. “That’s why I think you hang on to Shakespeare and you hang onto Great Gatsby. They’re culture; those cultural touchstones are important.”

Cultural significance aside, teachers like Menlo-Atherton English teacher Kat Keigher have decided that if they don’t have to, they aren’t going to teach certain classics.

“Part of the reason why I’ve started to phase [Great Gatsby] out of my curriculum is that I simply don’t think it is the best representation of the historical era or the writing of the era,” Keigher said.

Gatsby is required in regular English III, and AP English classes around the nation because of Fitzgerald’s representation of the Jazz era and America during the 1920s.

“For years, Gatsby has been considered the iconic American novel, not just of the 20s, but of all time; my problem with this is that if students read Gatsby thinking it is representative of the era and the nation at the time, they’re not getting the whole story,” Keigher said.

F. Scott Fitzgerald is the mastermind behind the classic, and is in fact, a dead, white man.

“[Gatsby] is also the limited history of privileged white people, written by a privileged, anti-semitic, racist, [and] white man,” Keigher said.

Diversifying the content taught in her class is Keigher’s main objective; giving students the same content that they would learn with Gatsby, just through a different lens, can pose its challenges, but if it means engaging students with an inclusive, diverse curriculum. It is worth it in Keigher’s eyes.

“Since realizing how much of what I teach is just passed down from what I read as a student, I have actively tried to diversify the narratives and perspectives within my curriculum,” Keigher said. “As a teacher, this poses a challenge because of course it means reading new books, prepping new curriculum, designing new assessments, etc.”

Reshaping the curriculum for all English classes would not be a far-fetched idea based on some of the public’s current views on what’s taught in class. Introducing more diverse voices and literary pieces is an option.

“If I could reshape the curriculum, I would continue to diversify both the voices (authors, characters, etc.) and the issues that the texts address, and I would encourage other teachers to do the same,” Keigher said.

Fitzgerald’s representation of materialistic ideals in the 1920s Jazz Age is one of these “cultural touchstones” that societally justify the continuity of teaching books like “The Great Gatsby.” As society progresses, how new authors and literary pieces are implemented into the modern curriculum is still up in the air because it would mean reshaping pop culture.

“These works [that] we consider a part of pop culture are by the white males we’ve already agreed on,” Reibstein said. “So how are we going to find new ones? Toni Morrison is probably a good example of a black female author that everybody agrees is incredible.”

Another interfering factor with progressing towards a more well-rounded, contemporary curriculum is the heavy influence of “cancel culture.” The 21st-century term has grown to popular use over the last few years and is developing a negative reputation for “canceling” various people and books.

“Cancel culture from the right; that sensory stuff is insane, they are literally forbidding the teaching of slaves at certain ages, or gender discussions about gender choice, and it’s crazy,” Reibstein said.

Evaluating history from a modern perspective is important regardless of how old the literary device is. History consists of real events; censoring events from the past would consist of teaching a sugar-coated history.

“It’s history,” Haro said. “It actually happened. And if you’re just burying those things down, you’re burying all the sacrifices people made, all the people who died, and everybody who was hurt during that time.”

Cancel culture’s influence on the literary world is growing; this is evident through the “canceling” of Dr. Seuss books, and the “Harry Potter” series by J.K Rowling.

When parents hear about the mature and graphic content their children are reading in class, it tends to raise some red flags.

“I don’t see how the truth harms their children,” Ken said. “They’re objecting to the visual images in [Maus], but I have to question; are they then objecting to all the violent images in video games that their kids are playing and all these other things, or is it just that topic? I just don’t agree with it.”

Syllabuses are passed out to students for every class at the beginning of the year that parents have to sign, and for English classes, they always include the content that will be read and watched.

“If you are coming from a position of authority and you’re giving something to a minor, I think parents need to be aware of what’s going on,” McDevitt said. “Parents should be involved in the decision-making process, but any younger student with internet access can find anything they want that’s extremely controversial in a matter of just moments, so I don’t know if you’re necessarily going to shield younger students from information they couldn’t get elsewhere.”

“The Giver” by Lois Lowry is one of the most popularly banned books. It was first banned in 1994 when parents complained about violent and sexual content.

“[In the Giver’] the society is striving for perfection. But in doing so, they are eliminating the things that make the people human,” Pretto said. “They lose their humanity in this quest for perfection, and I think that that is exactly what banning books is about . . .you can’t protect our children by limiting their access to knowledge.”

Between the lines of controversy and backlash for the teaching of certain literary pieces, striving for a more contemporary, progressive curriculum is becoming more and more widespread, especially in the Bay Area.

“We picked [‘Born a Crime’] because Trevor Noah is an author of color and I’m very interested in a sort of culturally responsive curriculum,” Dolan said. “Born a Crime was a contemporary choice; something that kids could connect to that they would be entertained by.”

The questioning of what should be taught lies in the connection between the author’s intention behind the usage of offensive language and execution.

“I think [society] is moving towards a point where there’s a lot more evaluation of texts,” Dolan said. “Trying to understand the purpose of the text justifying the use of the language is where I think we need to be.”

The banning of books is largely due to adults and parents opposing certain topics being exposed to their children. However, banning books may make them more desirable for children.

“Book banning is an ironic tactic, in my opinion,” Keigher said. “The forbidden fruit mentality is real, and the attempt at shielding children from something often just makes that concept or practice more appealing. Sheltering children from certain ideas feels safe for parents, but it can be detrimental in the long run.”