What makes art valuable? Ask an artist, and they’ll probably talk about brushwork, perspective, color, or a myriad of other topics. Ask an economist, and they’ll give you a much simpler answer: quantity. Anyone can try to copy “The Birth of Venus,” but there will only be one original, and limited supply increases demand. This system works well enough in the physical world, but what about the digital world? Online, where a piece can be screenshotted, recorded, and freely passed around, how can anyone know what’s original and what’s a copy?

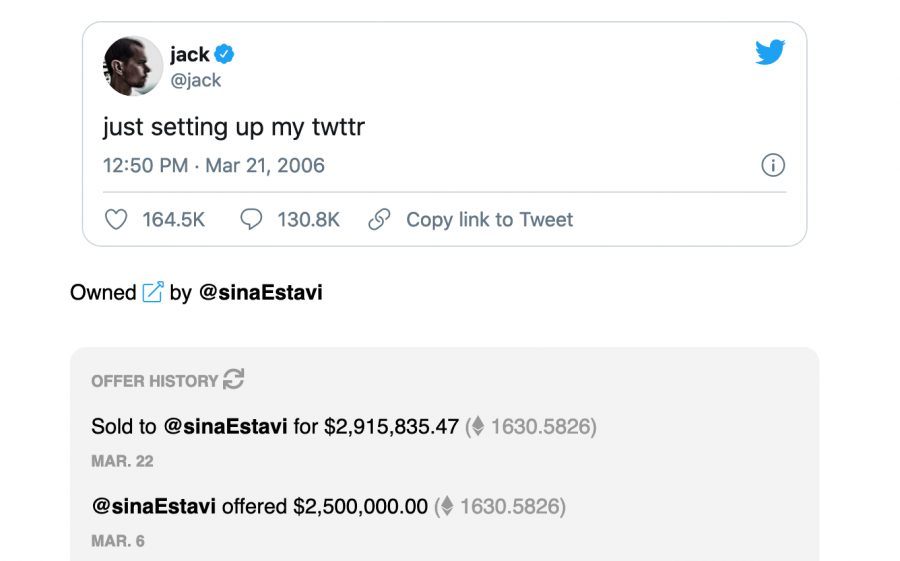

Take non-fungible tokens, or NFTs. NFTs exist as digital art, such as images, videos, or music, that are verified as authentic originals through complex computer processing. This means an NFT and a copy will have no superficial differences — they’ll look and sound exactly the same — but data will still claim the NFT as the “real” work.

Woodside senior Alexander Beaver, who has experience with NFTs through an internship and personal research, spoke to the Paw Print about what goes on behind the scenes.

“Writing and verifying transactions takes a lot of power, so there are networks of computers designed to help the process,” Beaver said. “Much of the computation happens on ‘server farms,’ or collections of dedicated computers with very powerful hardware.”

Server farms run “blockchain technology,” which is used to check transactions in the digital marketplace. NFTs utilize this system to keep track of which people own what art.

“The purpose of a blockchain database is to make it very difficult to forge any entries,” Beaver stated. “New transactions are grouped into a block, which is then sent to all of the computers that run the network to be verified. When it has enough verifications, a block is considered to be valid, and the process begins over.”

While some see NFTs as a win for artists, others have a different perspective. Woodside senior and artist Cole Torgeson thinks NFTs exacerbate the flaws inherent in art ownership.

“To me, no one can truly own art,” said Torgeson. “Art is an idea, as is the meaning of each piece of art. Art only has meaning because of our own personal interpretation. Therefore, I think the purchase of any kind of nonfunctional art (meaning art that doesn’t have some living purpose like a fashion piece or a building) is totally superficial.”

Torgeson further elaborated, stating, “The media being digital makes it all the more easy to see the pointlessness of art ownership, as it exaggerates exactly how little the ownership does. It’s essentially purchasing a title.”

Climate activists also have criticism for NFTs. The large server farms needed to run blockchain technology emit copious amounts of carbon dioxide, contributing to climate change. While no singular artist can be held responsible for the creation of these server farms, the continued sale of NFTs certainly warrants, and thereby causes, the farms’ existence. Artists need money to survive, but does that absolve them of any wrongdoings they support in the pursuit of wealth?

“Artists are as responsible for their carbon footprints as Uber drivers are for the exhaust of their cars,” said Woodside senior Guy Wilks.

Wilks argues that NFTs allow artists to profit from art and labor that would otherwise go unpaid. The issue, he says, has less to do with artists and more to do with the underlying systems at play.

“There needs to be better-built infrastructure on the electrical power grid that does not rely on fossil fuels,” Wilks stated.

As for the future of NFTs, Wilks has a few theories.

“The more that people know about [NFTs], the more that they tend to see its problems,” Wilks said. “I think that to some degree, the demand will grow significantly in the next couple of years, but is likely to taper off (and possibly even fall) if a better solution comes.”