In 2010, during her first year as Instructional Vice Principal of Woodside High School, Diane Mazzei was not expecting to face the press. But, following Woodside High School’s appearance in the award-winning documentary “Waiting for ‘Superman,’” Mazzei found herself answering questions for reporters from The New York Times, The Almanac, and San Mateo County Times on campus.

Directed by Academy Award-winner Davis Guggenheim, “Waiting for ‘Superman’” featured a variety of schools, including both public school Woodside High School (Woodside, California) and Summit Preparatory Charter High School (Redwood City, California). The film centered on the shortcomings of public education in the United States and evaluated the merits of charter schools, or schools independent of the state’s school system that receive government funding.

“It was my hope that people would look at charter schools as another option to standard public education,” Lesley Chilcott, the producer of “Waiting for ‘Superman,’” said in a statement to The Paw Print. “There was, and still is, a lot of misinformation out there about how charter [schools] actually work… After the film, I think people became more aware that charters are an option if they are performing well.”

Although Chilcott said the film was “received very well” by people from the “far-right and the far-left of the political spectrum,” a number of public educators felt like their voices went unheard.

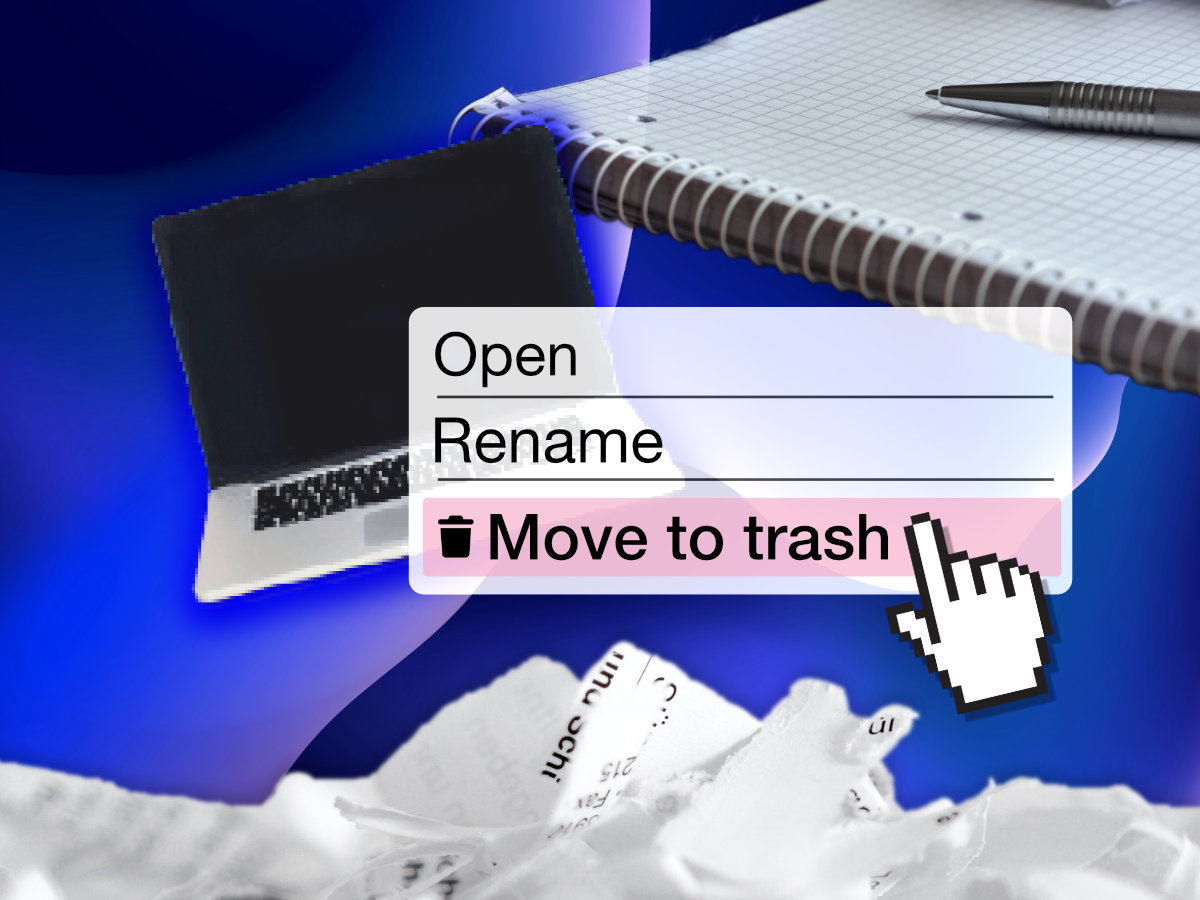

“I remember receiving an inquiry by the producers to come to our campus to get some shots of the campus,” recalled David Reilly, Woodside’s principal at the time. “When we realized they were doing a documentary on charter schools… I immediately offered the producers and the filmmaker to come in. If we’re going to be referenced in the film and used as a source of comparison, they might want to visit and get to know who we are… They weren’t interested. They declined.”

Since Woodside is a public school, the filmmakers arrived on campus after hours and drove through the parking lot to get the footage they needed. Woodside administration received no further news about the film until a concerned parent saw it in the January 2010 Sundance Film Festival.

“[The parent] said she was appalled at the representation of Woodside High School,” Reilly wrote in an email to the district superintendent, James Lianides. “She said she was sick to her stomach at the depiction of our school. I asked her if she thought it would upset me. She looked at me and said it would infuriate me.”

On September 24, 2010, the film premiered nationwide.

Though Woodside representatives were not invited to the first San Francisco screening, Mazzei, Lianides, Reilly, former parents, and board members attended anyway and raised their concerns with Guggenheim.

“If you’re going to tell a story and you’re going to make accusations, then you would at least attempt to talk to the school,” Mazzei told The Paw Print. “You would at least do your job and find out the facts before you broad-brush it. And that’s exactly what [Guggenheim] told us: ‘It’s a broad brush! Sorry about that!’”

One critique the documentary makes about Woodside is how it tracks students, slotting them for advanced or standard curriculum based on subjective traits such as neatness and obedience to authority aside from more objective factors such as academics. Conversely, at Summit Prep, all students take similar courses.

“We don’t track the students,” said Todd Dickson, a Summit Prep representative interviewed in the documentary, “because we think every kid should be able to get to the highest level of curriculum, so we want to hold them all to the same high standard.”

Ernest Lo, who has taught biology at Woodside for 20 years, felt that the documentary did not accurately portray how Woodside places students on different curriculum pathways.

“The movie’s portrayal of how Woodside was trying to educate our students in a more traditional fashion was totally against what I had been seeing at Woodside all this time,” Lo stated. “It’s nice that Summit Prep tries to prepare everyone for the advanced placement track or higher-level classes, but the reality is that a lot of the… parents that place their students [there] have probably emphasized education for their kids.”

The documentary compared Woodside to Summit Prep multiple times through citing statistics and describing curricular differences. According to the film, 62 out of 100 Woodside ninth graders would graduate in four years. Meanwhile, 96 out of 100 Summit Prep ninth graders would graduate in four years.

“They were very selective in the statistics that they used to feed their narrative,” Reilly remarked. “They were using graduation rates that didn’t factor in the transiency of our population… This was the time when the economic downturn was happening, so a lot of families were leaving. We were dealing with things that the charter schools weren’t necessarily dealing with.”

In an article from The Mercury News, Reilly cited what he felt was a more representative measure of Woodside’s success: 93 percent of graduating seniors went on to two- or four-year colleges.

Still, Chilcott explained that she and other documentary producers did not intend to portray charters as the best option for students.

“We tried to make it clear that charter schools are not the answer in and of themselves,” Chilcott said. “But the out-of-the-box thinking, the creativity, and the accountability that many charters have tend to make them very good. The good ones should be held up as potential examples for failing or average schools. But they are not the only answer.”

Regardless, the documentary drew national attention to Woodside and its curriculum. Some suspected that the film led to a slight decrease in Woodside’s enrollment, but the impact was never statistically proven. The main concern of Woodside staff was the press; following the film’s premiere, Reilly called a schoolwide teacher meeting to review protocol.

“He sat us all down [and] prepared us for what might come,” described Lisa Camera, a Woodside English teacher of more than 30 years. “We had journalists on campus [and] people trying to penetrate the walls to get in and talk to kids and talk to us… Honestly, I think it could have been a lot more chaotic and difficult, but because of that more proactive way of dealing with things, it wasn’t as bad.”

Reilly noted that, as the principal, he felt responsible for reassuring his staff that the school’s reputation would remain intact.

“I was trying to build and sustain morale,” Reilly explained, “and I wanted the staff to know that the site administration and the district had its back, and that we were going to do everything we [could] to tell the true narrative and educate the public about the complexities of this comparison.”

Despite Woodside’s initial struggles with the press, Camera noted how the film actually helped unite the Woodside community.

“The parents really rallied behind us, and the community did too,” Camera said. “I think they recognized that… the reality was not what the documentary presented.”

Through hosting parent tours, strengthening their shadowing program, and speaking with media outlets, Woodside reframed their public image and even saw increases in enrollment.

“In the end, we took on this challenge, and we came out stronger,” Reilly emphasized. “As stressful as it was and as surreal as it was to be seeing… this nationally-distributed film take shots at the school that you’re leading, we ended up turning it into quite a positive because it gave us quite a platform.”

The publicity gave Woodside the opportunity to bolster and promote programs such as audio production and advanced calculus, along with facilities such as the science labs and the digital media center.

“Once we got over the upset, we went right to work and just started telling our story,” Mazzei said. “I think we really represented our school well, and I feel as if the traction that the director had hoped for by bashing a public school never took off. It wasn’t able to destroy us.”

Ninety percent of American students attend public schools, and yet since the rise of charter schools in the early 1990s, some have opted for alternative options due to their specialized—and often more individualized—curriculum. One local charter school, Summit Prep, is a mere 14-minute drive from Woodside High School. It aims to “prepare a diverse student population for college and to be thoughtful, contributing members of society.”

Founded in 2003 by the charter management organization Summit Public Schools, it has fewer than 500 students and offers a Personalized Learning Plan (PLP) with mostly individual online courses.

“How we approach education is unique,” stated Summit Prep Executive Director Caitlin Reilly. “Last year, every student graduating from Summit Prep met the state’s A-G standards, California’s way of measuring college readiness. Also, all Summit Prep students graduating in 2019 were accepted to college. We’re proud of the continued success and the opportunity to provide this public school option.”

Unlike most public schools, all Summit Prep students take the same core classes, which include a minimum of six AP classes. Additionally, rather than having elective classes every day, students take two-week elective courses every six weeks.

“Many community members of San Mateo County recognize students succeed in different environments and are working to ensure those options are available within our local public schools,” said Nadine Abousalem, Summit Prep’s Communications Director, in a statement to The Paw Print. “Summit is proud to be among many strong local public options.”

In 2010, Newsweek ranked Summit Prep as one of the top ten high schools in California and one of the top 100 high schools nationwide.

“Newsweek’s acknowledgment of Summit Prep as a top 100 high school in the country is a testament to the success of our academic model,” Summit founder Diane Tavenner said in a written statement to The Mercury News.

Yet despite taking a variety of advanced classes, Oriana Smith Anderson, who transferred from Summit Prep to Woodside in 2016, recalled having “basically no homework.” After less than five months at Summit Prep, she had already completed the entire semester’s classes online.

“I felt like I was almost in middle school, but I was supposed to be in high school,” Smith Anderson, who is now a senior, said. “Every single grade in my classes was an A+, and it wasn’t a testament to how hard I worked.”

Despite having an online curriculum that allowed her to work at her own pace, she felt she wasn’t learning. In hopes of preparing herself for college, she decided to transfer to Woodside.

“The workload is not enough,” Smith Anderson declared. “If you go to college on a Summit education, you will not succeed because you haven’t been working at the level that is required of college students.”

“We have a lot of people who have graduated and gone to big universities and dropped out to go to a community college because it was just way too much from them compared to Summit,” current Summit Prep senior Eliza Insley explained. “[Summit] doesn’t hold us very accountable, so applying those skills in the real world… is kind of overwhelming.”

Still, both Insley and fellow Summit Prep senior Casper Lyback enjoy the freedom of taking online courses at their own pace.

“It gives you a lot of independence and, in a sense, does prepare you for the independence that college brings,” Lyback stated.

In 2010, inspired by Summit’s positive portrayal in “Waiting for ‘Superman,’” current Woodside English teacher Lisa Prodromo moved from Chicago to the Bay Area to teach at Summit Prep.

“There’s this local high school Woodside, and people aren’t graduating,” Prodromo described, recalling her initial impressions of the film. “And here, you have Summit — kids are taking AP classes, they’re a little community, everyone is passing and working independently.”

Five years after Prodromo, current Woodside Spanish teacher Amy Hanson also moved from Chicago to work at Summit Prep.

“[‘Waiting for “Superman”’] made me feel extremely inspired to do something different, to be part of something changing the face of education,” Hanson said. “They were ‘revolutionizing education’… They were in all these newspaper articles… and I thought, ‘I’m moving across the country to work at one of the best, most innovative schools.’”

Hanson began working at Summit Prep as a Spanish teacher, but she soon found that she was expected to be a counselor as well. Students are assigned to a mentor group with about 20 other students, and their mentor (a teacher) helps them with academics, college, and personal issues.

“On paper, it sounds like a phenomenal idea,” Hanson said. “Imagine you’re a freshman who gets assigned a mentor group; you have a teacher to help you during all four years.”

“My mentor group is really close with our mentor and with each other, and it is one of the best things about Summit,” Insley described. “If [mentors] don’t have any knowledge or training in [counseling], there is only so much they can do, but it is great that you always have an adult you can go to for support.”

Although students might feel supported by Summit Prep’s mentor program, Hanson felt overwhelmed by the responsibility to teach, support students’ mental health, and help them create four-year college plans.

“It turned into not just a mentor group but basically becoming a surrogate mother or father,” Hanson said. “The teacher is bombarded throughout the day, and that’s what really put me over the edge.”

Though Hanson tried to adjust to Summit Prep’s teaching style for several months, her physical and mental health declined rapidly. In December 2015, she finally realized the toll her job had taken on her.

“My husband sat me down and was like, ‘I’ve never seen you like this before,’” Hanson said. “My hair was falling out, I had gained 20 pounds because I didn’t have the opportunity to take care of myself; I wasn’t sleeping. I had to stay [at Summit] until 5:30… [and then it was a] two-hour commute [back home]. It was horrific.”

Hanson began exploring other teaching opportunities and eventually joined Woodside’s staff. After working at Summit Prep for a year, Prodromo was similarly disenchanted.

“They emotionally break down teachers; at Summit, there’s no value in the art of teaching,” Prodromo said. “Summit had this motto, ‘we do more with less,’ and that’s a terrible thing to say: ‘I’m going to deprive my students of basic things they should have, like a library and a counselor.’”

When she saw an open teaching position at Woodside, she recognized the school from “Waiting for ‘Superman’” and applied. Four days later, she landed the job.

Since their inception, charter schools have been the source of controversy within the American educational system, with some arguing that they detract from the resources meant to support public schools and, due to their sometimes business-like structures, may even take advantage of lower-income students.

“In America, it’s much, much harder to get into college if you don’t have that foundation of income,” Smith Anderson reasoned. “There’s this desperation among lower-income students to get into college and have those perfect grades, the perfect GPA, test scores, and Summit preys on that by promising inflated grades and promising college prep when they don’t deliver that.”

Still, others feel that charter schools can be a beneficial alternative to students who could use more personalized support.

“My goal as an educator is to try to do the best job serving the students that are in my classroom,” Camera explained. “Charter schools are designed to serve students who don’t necessarily fit in, so they serve an important purpose… If there’s a student that gets a better experience at Summit, then all the power to them.”

Although some argue that charter schools detract from the resources meant to support public schools, David Reilly acknowledged the funding complexities that blur the lines.

“I think as long as children are happy, and they’re learning and flourishing and growing, I don’t have any feelings that are opposed to charter schools,” Reilly said. “There are so many challenges in the world of school finance that I don’t think it would be fair to just point at charter schools and say they take money from public schools. It’s a little more complicated than that.”

Ultimately, regardless of its depictions of public and charter schools, “Waiting for ‘Superman’” provoked discussion about issues that remain relevant a decade later.

“‘Waiting for “Superman”’ highlighted the desire for more high-quality education options and the sense of empowerment it provides a community,” stated Abousalem. “What we’ve seen since, especially in San Mateo County, is a push for choices.”

Mark Reibstein • Mar 10, 2020 at 2:32 PM

Waiting for Superman was part of a larger “reform” movement, funded for the most part by an alliance of business persons, politicians, and like-minded academics who thought public education could not innovate (as the tech sector — or, for that matter, any market-driven sector – could). Here’s what was missing from that film: the professionals who actually spend their days with students, who devote their passions and time to education – public school teachers and administrators. Someone described the film as nauseating. That was my response, though I couldn’t at first figure out why. I was excited that a film about education was getting prime-time attention. The day after seeing it, though, I realized that a microphone had never been put in front of a public school teacher (nor, for that matter, as Mr. Reilly attests, were WHS administrators permitted to contribute).

This “reform” movement began with calls for standardization and teacher “accountability” that crested with No Child Left Behind (Get-tough-on -teachers DC Superintendent Michelle Rhee was a hero in the film – if only teachers could all be on the same page, the problems of education would be solved!). Whereas charters were originally conceived of as places for innovation, where public school teachers and administrators would be empowered to make change in smaller, less restrictive communities, the movement was co-opted by these new reformers. The “billionaire boys club” (as some called them) behind the film truly considered themselves world-saving supermen. Allied in particular with technology corporations, the new reformers sought to make an end-run around educational professionals they considered hapless, opening public coffers to profit-making (supposedly innovative) corporations. The film’s opening was a staged event in Newark, with then-mayor Corey Booker, on the Oprah show, where Mark Zuckerberg gave one billion dollars to fund for-profit charter schools there. Within a few years, that money had evaporated, enriching corporations, but not improving education in Newark. Zuckerberg learned his lesson, realizing he should work with educational professionals in the public sphere, and he subsequently brought his money much closer to home, beginning the discussions that have led to our district’s Tide Academy (I assume he’s still a backer, if not the principal one from outside our district, but I don’t know if my information is up-to-date).

The film and reform movement get some things right: our systems do serve some students more successfully than others, and hierarchical structures, from the state to the classroom (including union/management roles), rigidify pedagogy and can prevent teachers and administrators from working together to regularly reassess the problems students face and truly innovate to find new solutions. But charters have had comparable results taking on those issues. More importantly, accusing WHS of serving an elite, just like blaming low test-scores on teachers, is a way to avoid the huge social problems (principally the result of economic inequality), which shape the conditions within which public schools operate. If you want schools and teachers to remake our society, you must empower, ennoble, and fund those professionals who show up every day to perform their sacred trust – not restrict, blame, or divert funding from them.

Raphael Kauffmann • Mar 10, 2020 at 11:18 AM

Well done! I think you presented the many sides to this issue in a balanced way. I remember seeing this film while I was teaching at Carlmont and thinking that it presented an exaggerated “do or die” situation for students entering the Summit “lottery,” that if they didn’t get in, they would fail in life. Having taught here now for 7 years, and seeing students go on to a diverse list of post-secondary choices – from 2-year community colleges like Canada, to 4-year universities like Stanford, or straight to work, I know that Woodside prepares students for the variety of options that life presents.