Earplugs, pens, soap, tape, and razors: what do these products have in common? Many are commonly marketed separately towards men and women, revealing underlying gender stereotypes.

When marketers try to appeal towards a certain gender, they use common stereotypes about that gender. Woodside sophomore Ben Shepherd, who identifies as male, saw that a common stereotype towards men is the way they are expected to act.

“It has a lot to do with emotions,” Shepherd said. “There’s a lot of pressure to be super gentleman-like or polite to other women. A lot of it is just acting very masculine.”

Woodside freshman Mandy Hespelt, who identifies as female, also sees gender stereotypes in the way women are expected to act.

“I guess the stereotypical woman should always be polite and have good manners,” noted Hespelt.

Students also saw color as another common stereotype used to distinguish genders.

“I would definitely say that there are some things where it’s like pink [is] girls and blue [is] boys, and it’s just kind of divided like that,” voiced Rei Mead, a Woodside sophomore who identifies as non-binary.

“For little kids, like girls, their [toys] are very pink,” added Woodside sophomore Sarah Steinmetz, who identifies as female.

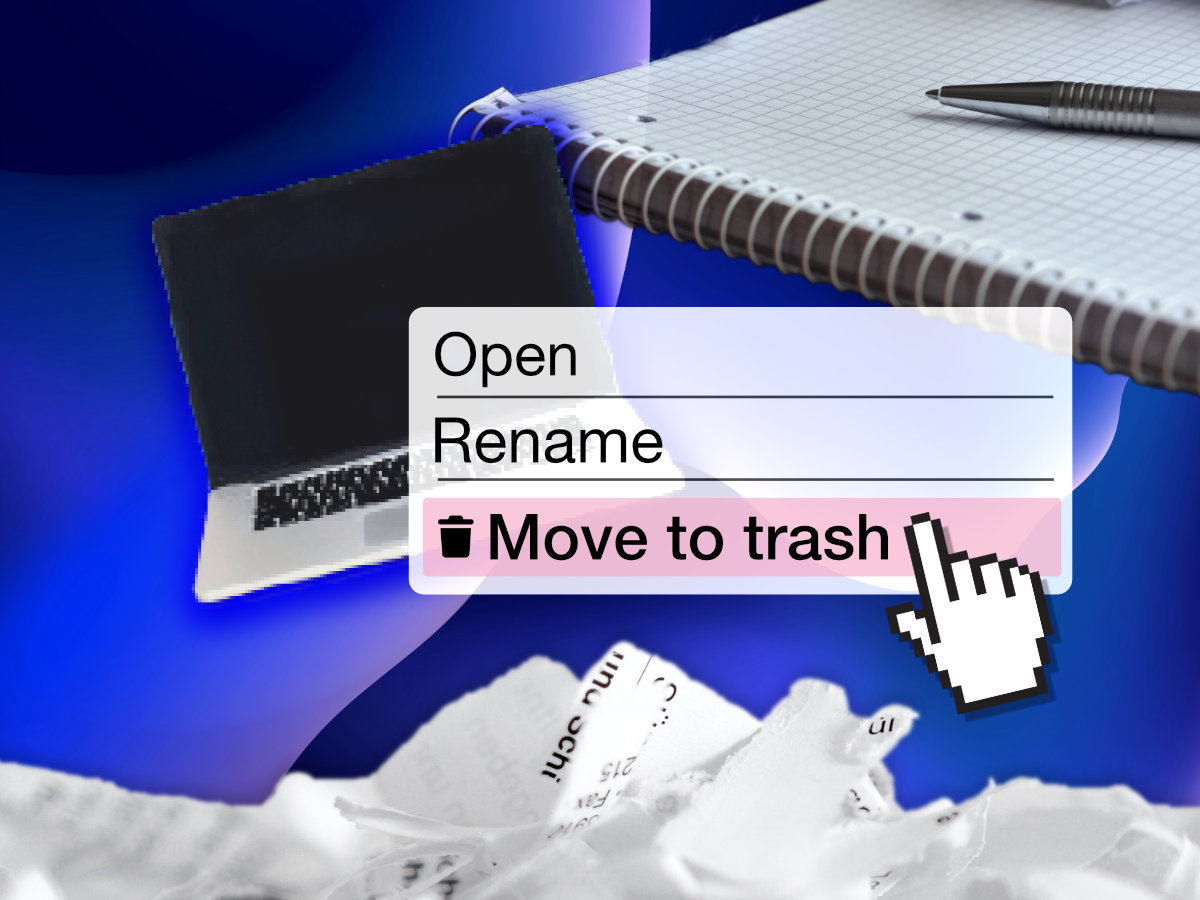

One phrase that has gained prevalence is “pink it and shrink it,” which refers to the way companies change their products for women by making them pink and smaller. Woodside senior Jet Thipphawong, who identifies as genderfluid, also noticed that corporations unnecessarily gender certain products.

“[Corporations use]… completely gendered marketing [towards] things that are completely ungendered…. like gendered candies and stuff… that [has] no difference, other than the color,” said Thippawong.

Woodside sophomore Kai Steiner points out more gendered products.

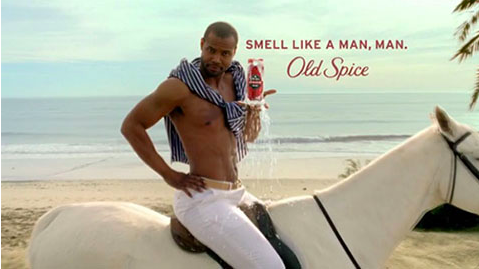

“The female Dove ads are all elegant and beautiful, and then there are the male ads where they’re literally so masculine,” said Steiner, who is male. “Why do they have different soap ads in the first place? Isn’t it just soap?”

A woman’s soap add from www.orialimara.com displays stereotypical women marketing.

Woodside French teacher Gay Buckland noticed that certain products are marketed towards certain genders. One example she observed was a car ad.

“[A man and a woman] go out in front of the house, and there is an SUV parked next to the big truck,” said Buckland. “She goes straight to the truck and says, ‘I love it, thank you so much.’ The whole joke is that it was obviously for him.”

Gabriel Perez, a Woodside freshman who identifies as male, noticed that a lot of his ads on Instagram were geared more towards stereotypical male content.

“I don’t really use social media that much, but I just get a lot of skateboard ads on Instagram,” said Perez.

Steiner also noticed companies have used gender as a way to sell toys to kids.

“When you shop for toys on… Walmart or Toys“R”Us, there’s a distinct search where you can pick the gender,” said Steiner.

Woodside sophomore Audrey Jacobson did not find problems in marketing towards a certain gender, with certain restrictions.

“Well, it depends, as long as it’s not offensive,” stated Jacobson. “It shouldn’t make anyone feel uncomfortable, but you also have to sell your product. So there’s a fine line in between where it’s funny and against the customer to buy a product.”

Shepard agreed, citing similar reasons.

“If it gets to a point where it’s over the edge, and it’s really just placing a really huge stereotype on a certain gender, that would be a problem,” noted Shepherd. “But if it’s selling the product you’re trying to sell, I don’t really have a problem with it.”

Meanwhile, Steinmetz thought gender-oriented marketing could have a negative impact on its young audiences.

“Sometimes it helps sell the products, so I guess it helps out the marketer,” said Steinmetz. “But I don’t think it’s a good thing to be forcing it on little kids’ brains.”

Buckland saw the effects that these common stereotypes can have on young children.

“I think it limits a child’s ability to create their own identity,” said Buckland. “I think that it makes a kid feel that if you’re a girl who doesn’t mind playing with a monster truck, then you’re doing something that [you’re] not supposed to, and the converse is also true. I think it limits what someone is supposed to feel comfortable in, and that’s a shame.”

Steiner is one example of someone who does not fit the common masculine stereotype.

“I don’t really have super masculine toys,” noticed Steiner. “I don’t pick products based on gender. Growing up, I never was into cars. I’d rather have feminine toys.”

While gender stereotypes can still be commonly seen in marketing, society’s views on gender have evolved a lot over the years. Some students noticed a resulting shift towards more gender-neutral products.

“There’s a big movement on gender neutrality right now,” said Shepherd. “I think [companies are] trying to… make it more neutral. I’ve noticed because I haven’t seen a lot of commercials that… are designed for women. It’s a lot more neutral in marketing.”

While Buckland has also witnessed the move towards gender neutrality, she believes some aspects have failed to progress.

“In some areas it has gotten better, but in some, the divides are just as big as it’s ever been,” voiced Buckland.