As a recently-minted 18 year-old who voted for the first time just a few months ago, I can say with confidence that voting is not the exciting mutual enterprise that I had imagined. My parents have long told me stories of how, back in 2008, they waited in hours-long lines with me in a stroller to vote for the President. They would recount how, for that day, voting and participating in our democratic tradition became their sole task, the focus of all of their attention. For them, back in 2008 voting had an air of solemnity to it. It felt like an expectation worth waiting for the chance to live up to. It felt not just like a privilege or a task, but a core duty attached to citizenship in this country. But what was true then is not true today.

When I voted in the March primaries, I didn’t wait in a line. I strolled into a dreary room in which I was one of five people, three of which were employees. I filled out the required forms, submitted my ballot… and left. Not quite the societal undertaking my parents wistfully describe.

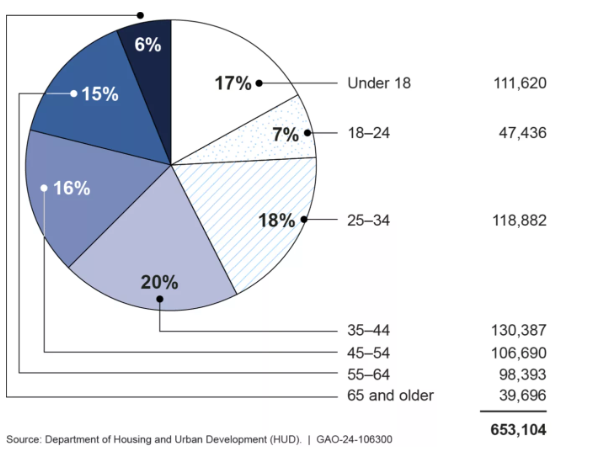

The reason for this is primarily twofold. For one, voting participation rates in America aren’t great. In 2020, for example, 62.8 percent of eligible Americans participated in an election. That may sound high, until you hold it against other democracies worldwide. In the same year, New Zealand saw a 77% voting participation rate. In Uruguay during 2018? 90.1%. Furthermore, young people, the demographic with the most at stake in any given election, tend to have lower turnout rates compared to older generations. What this means is that, far from being a mass collective enterprise, only just over half of Americans meaningfully participate in our core democratic ritual, and most of those tend to be older.

The second reason voting feels more alienated and ordinary now than a decade ago is the precipitous rise of vote by mail and early voting. In the 2008 presidential election, just 30.7 percent of votes were cast via these methods (termed “nontraditional methods” by the US Census). By 2020, the year of our most recent presidential election, almost 70 percent of votes cast are through those nontraditional methods. Now, these ways of voting have clear benefits, of course. Allowing citizens a greater range of ways to vote makes it easier for people with demanding jobs or parenting schedules, illnesses, travel plans, or other impediments to still vote. But it does have a certain cost, one that isn’t necessarily quantifiable, and thinking about that cost provides a window into how we can make our elections better cultivate a democratic spirit.

In her 2022 book Election Day—reviewed by me in 2022—Stanford political scientist Emilee Booth Chapman set out to answer an ambitious question: what is the psychological role of voting in our collective democratic experience in America, and how can voting be reformed to better cultivate said experience? To quote her at length:

“[V]oting makes salient the fact that modern democracy is a mass collective phenomenon. Voting is irreducibly something we do together. It serves as a reminder that our political agency depends on joining together with others. The practice of popular voting, then, especially when it conforms to the ideal of approximately universal participation, provides an occasion for the community to express its commitment to democracy’s core values of political equality and popular sovereignty, and for citizens to affirm and participate in this expression.”

What she is saying here is simple: voting, when done correctly, together, at the same time, and en masse, as my parents did in 2008, provides an opportunity not just for citizens to involve themselves in democracy but to also see all of their friends, community members, and fellow citizens doing the same.

This shared experience is valuable for a multitude of reasons. For one, when we see—yes, literally see, with our eyes—a mass of our fellow citizens all voting together, it reinforces to us the fact that the product of the election is the product of all the people, not just the product of the hyper-politicized figures we see on TV and on social media. Furthermore, voting that approximates universal participation creates a social expectation that we are supposed to be participating in democracy, elevating voting from a mundane errand we do every few months to an essential ritual endemic to being a citizen in America. Voting should feel different than getting groceries or depositing a check at the ATM. Lastly, in an election where you see everyone around you voting, the importance of voting, and thus of democracy, is impressed upon you—if everyone around me is voting, you think, this must be important. The key idea here is, as Chapman says, that “[v]oting creates democratic moments whose value is not reducible to the value of the information contained in the ballots.”

As detailed above, though, we do not have such elections in this country. For Chapman, the ultimate election is a periodic moment of “approximately universal” simultaneous turnout. We have the “periodic moment” part down, but the other elements, not so much. For one, our elections do not even get close to approximately universal turnout. As detailed above, only about 60 percent of eligible Americans vote. And voting in America isn’t simultaneous due to nontraditional voting methods like vote by mail and early voting. These factors preclude the unique momentousness and spiritedness, the shared experience of participating in democracy with all of your fellow citizens, that Chapman describes the possibility of. What to do?

The answer is pretty simple. There are three main reforms that would allow our elections to engender the psychological benefits that they have the potential to foster. First, make Election Day a federal holiday, so that no person is excluded from voting because of work or school. Second, eliminate nontraditional voting methods such as vote by mail and early voting in order to create that special shared democratic experience that only a momentous election can provide. Of course, there would have to be extensive loopholes to that regulation, for the bedridden, military, those overseas, and anyone else that for whatever reason absolutely cannot make it to the polls on election day. Nonetheless, the law should enforce the expectation that everybody without an excellent excuse must vote on the same day.

Lastly, and most controversially, voting should be made compulsory. This is something that Chapman has argued for at length. While that may seem overly burdensome at first, consider its relationship to the previous two reforms. If voting takes place on a holiday, and everyone is doing it at once, voting is already “the thing” that happens on election day. It’s the prime focus. It doesn’t seem unreasonable to then go and simply require that, on a day without work or school, on a day where citizens that want to vote have to vote, every citizen must vote. This reform makes even more sense when you realize that, alongside the previous two reforms, it would create the period moments of approximately universal participation that will allow for the unique psychological benefits of voting.

Voting, right now, is a chore. A job. A box on a calendar, an item on a daily checklist. But it should be more! Voting should be an experience. It should impress upon the citizen that democracy depends on them, that the will of the people is paramount, and that democracy is a shared endeavor, not an individual errand.

Take a second and imagine what this would look like. Congress has recently passed the trio of reforms mentioned above. Everybody you know is voting, because they have to. Nobody you know, including yourself, has work or school on election day. And, because of the elimination of early voting, everyone has to vote on the same day. Try to sense what that would feel like. Try to imagine the anticipation of the upcoming election, try to feel the singular importance of ‘next Monday,’ or whenever the election is. Then, skip forward. You wake up on election day. Democratic spirit saturates the air. You walk out your front door and see all of your neighbors leaving early to get a spot in line. It feels important. It feels momentous. It feels shared, mutual, even intimate. That’s what elections could be.

For now, though, we are left with a sleepy empty event space haphazardly draped with red white and blue flags, filled only with the noisy hum of an AC unit. You’re the only one there, because everyone you know voted last week, or voted by mail, or maybe didn’t even vote at all—there’s no way to tell, after all.