Para leer este artículo en español, haga clic aquí.

As the school year comes to a close, Woodside’s profile for 2018 to 2019 reflects a fairly racially diverse student body. The majority of students are either Hispanic (49 percent) or white (40 percent), with black, Asian, Pacific Islander, and mixed-race students composing the remaining 11 percent.

Yet Instructional Vice Principal Diane Mazzei offers a contrasting perspective within the classroom. Despite forming a majority of the student body, Hispanic students are a minority in Woodside’s Advanced Placement (AP) classes. During the 2018 to 2019 school year, 39 percent of AP students were Hispanic while 57 percent were white.

This disparity can lead a number of students of color, including one anonymous Woodside junior currently taking AP English Language, to feel out of place. The anonymous student comments that this lack of belonging began before even reaching AP classes, though. She received a culture shock when coming to Woodside from her middle school, East Palo Alto Charter School.

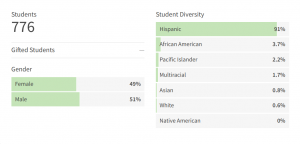

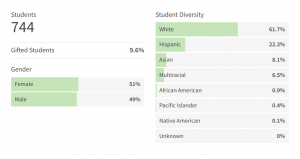

Demographics from East Palo Alto Charter school.

“I had never been to school with a person who was white until my freshman year in high school,” the student described. “I was always surrounded by people of color in East Palo Alto. But my [Woodside] classes [were] primarily white, and I felt a little different.”

At East Palo Alto Charter School, 91 percent of students are Hispanic, and 87 percent receive a free or reduced lunch. Due to this, the student added that race was not the only factor in her discomfort; she did not feel that East Palo Alto’s underfunded schools were able to adequately prepare her for AP classes.

“I did not have a math or history class in seventh grade and no science class in eighth grade,” she recalled. “We would have, if not less, 15 minutes of homework a night. Woodside is at least three hours of homework a night for me now.”

Meanwhile, Allison Smith tells a different story. Smith, also a Woodside junior taking AP English Language (among a number of other AP classes), attended Roy Cloud Elementary in Redwood City from kindergarten to eighth grade.

“I felt like [Roy Cloud] prepared me because I had been in upper classes,” Smith reflected. “There was an advanced math program, and through that program, I was able to start my freshman year in Algebra II Trig… I felt like I was challenged at school, and I was always pushed to work hard and aim for A’s.”

Demographics from Roy Cloud Elementary School.

In comparison to East Palo Alto’s median household income of $58,783, Redwood City’s is $99,026. Roy Cloud is also 62 percent white, and only 7 percent of students receive a free or reduced lunch. This high socioeconomic status results in the school receiving a lot of funding, and students enjoy activities such as field trips to Yosemite and Washington, D.C.

“A lot of [the funds] came from the parents of the class,” Smith explained. “I know a lot of my friends were well-off.”

These two differing perspectives have results reflected nationwide: according to the Connecticut Mirror, only 10 percent of students from low-income families take at least one Advanced Placement course, in comparison to 25 percent of students from middle or high income families.

Another group at Woodside that faces a particularly notable challenge is English learners, who form 12 percent of the student body. Yet Woodside art teacher Julie Marten notes that, although these students may not enroll in academic AP classes, AP Studio Art is an attractive option.

“Many of my best students can barely speak a word of English or are just learning it this year,” Marten described. “Your abilities and your success in AP Studio Art is not dependent on your language skills nor on your academic abilities.”

Still, Marten sees fewer students of color in her advanced art classes.

“Students tend to be, for the most part, mostly Caucasian and mostly taking advanced classes,” Marten stated. “This is a little bit distressing to me, but with administrative changes… I expect to see far more students of color to go into AP Art.”

According to Woodside counselor Katrina Rubenstein, English learners and other students in support classes face an intense schedule, often having no room for elective classes. The administrative changes that Marten mentions would allow these students to take more electives, which she feels provide an outlet crucial for success.

“Access to electives will be the thing that will increase diversity the most in advanced programs,” Marten commented. “If you struggle with language, you’re bound to get exhausted over the course of the day… In order to strengthen [students’] academic English, having that break is very important.”

Mark Reibstein, a Woodside English teacher, sees first-hand how some students struggle with the language and notes the demographic difference between his various English classes.

“Students in my English support class tend to be mostly Hispanic,” Reibstein described. “[In AP English Language], last year was a good year for minorities, but this year it’s less diverse again.”

To better integrate classes, he proposes an overall change in the education system, one that reduces the emphasis on the “social capital” of AP classes and instead places all students in the same classroom, separated into “threads.”

“Education is a top down structure; policies are created by those who have privilege,” Reibstein remarked. “You can’t have a system that uses these policies, because there are so many students from different backgrounds that bring in their own ideas.”

Reibstein also notes that classroom discussions about these social issues are critical to addressing and reforming them in the future.

“Students with privilege need to start talking about it,” Reibstein stated. “And students who don’t come from a place of privilege need to learn about why they don’t have privilege.”

According to Reibstein, teachers have the power to lead such a change and must realize their potential as educators.

“At heart, I think all teachers are idealists,” Reibstein said. “I don’t think there’s a single teacher who entered the field because they didn’t want to help kids… [But] a lot of teachers walk around waiting to be told what to do. Department meetings tend to be about ‘how can we implement this structure’… We need to start seeing teachers as activists and problem-solvers.”

Ultimately, the anonymous student approves of the support classes and programs that Woodside offers to students of lower income households, English learners, and underprivileged students of color. Still, she hopes to see better representation of a variety of perspectives in the administration in hopes that greater diversity in AP classes will follow.

“I think Woodside does its best, but the people who are in charge don’t really understand minority students and people who came from underprivileged backgrounds,” the student claimed.

Although the student continues to push herself to take advantage of the advanced classes Woodside offers, a number of her friends from similar backgrounds take mainstream ones, and she understands the appeal.

“There’s a lot more students of color in general classes than in AP classes,” she concluded. “I know if I took general classes, I would feel more comfortable.”