If you are plugged into the news of the Sequoia Union High School District, you have probably heard the word “detracking” thrown around in the past few months. Detracking is a major political issue within our district, and primarily because it is deeply relevant to all SUHSD students. With an important board vote on the matter coming up on November 15, this issue remains as relevant as ever. This article will provide context, a concise history of detracking within the district, and the current state of the debate.

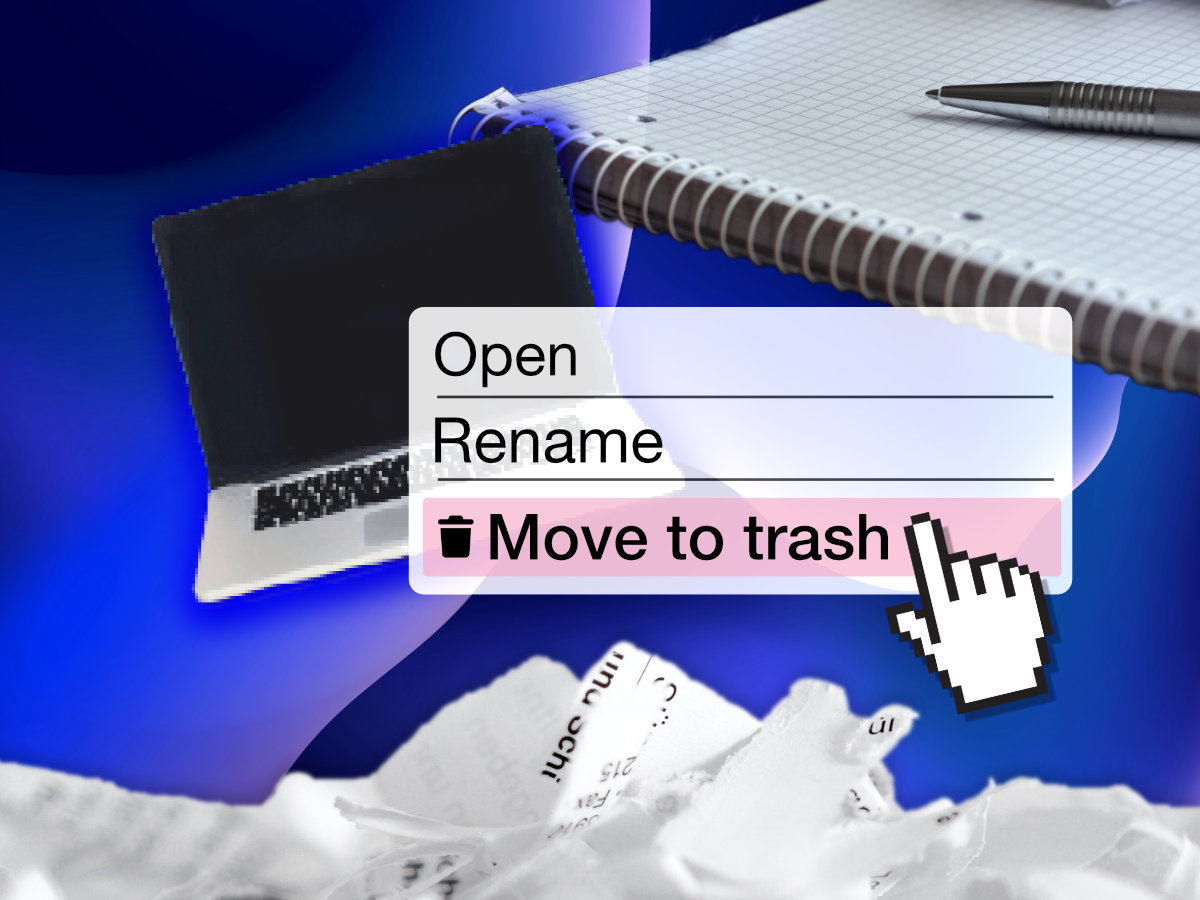

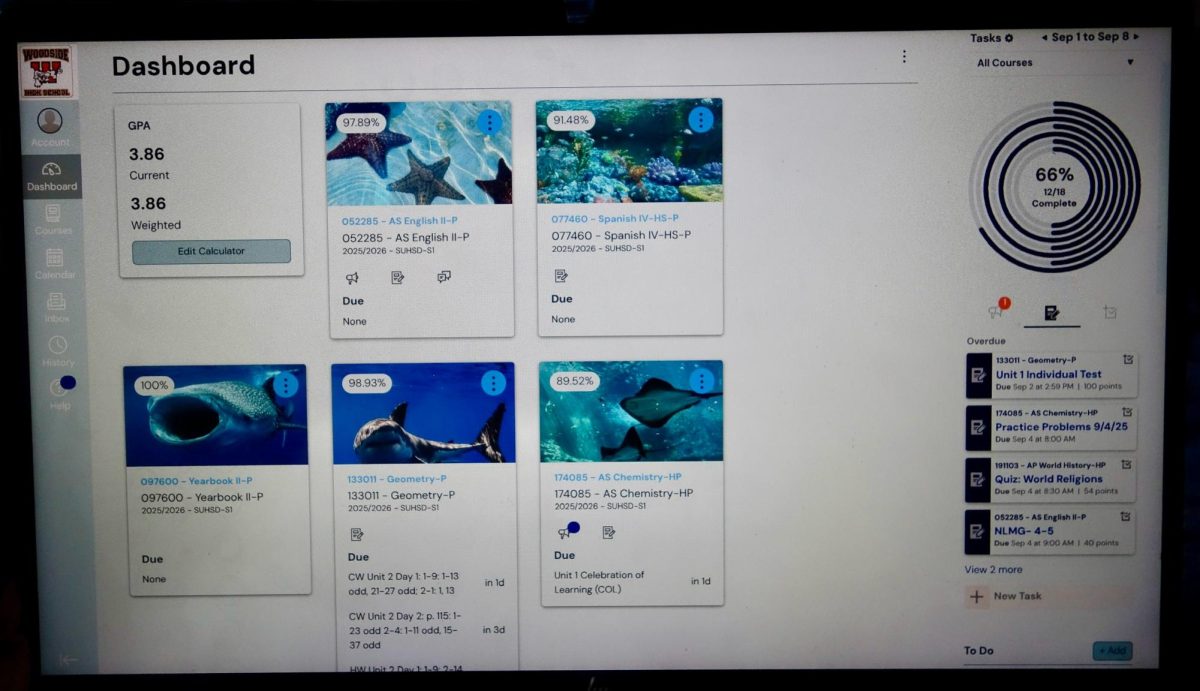

Detracking is, simply put, the removal of honors, AP, or advanced classes from a curriculum. It is two tracks of a course combined into one, with the higher level course being removed. Within SUHSD, this has occurred in a few ways, though it is important to note that no AP classes have been detracked; only been AS or honors classes have been subject to removal. To briefly summarize: at Woodside, AS English I was removed in 2022 in favor of a unified English I track. Menlo-Atherton did something similar, combining their advanced and regular freshman English classes into a single class called Multicultural Literature and Voice. M-A has also detracked their AS Chemistry, AS Physics, and AS Biology classes. Carlmont also detracked their AS Chemistry course. A complete list of all recent detracking course changes can be found in this report.

“In our district, we do like to innovate and try new things,” SUHSD Board Member and former M-A student Sathvik Nori said. “Maybe 10 or 12 years ago, [detracking was] something we started trying. We did it slowly in small pieces at first. Now, I think we’re at the level where a lot of people are thinking maybe we went a little too far in this situation.”

While this topic has been contentious since the first signs of detracking began to occur in 2016, it rose to major prominence after a charged board meeting on September 20, which went on for seven hours before ending unexpectedly. At that meeting, a draft report about the impact of detracking on student outcomes was presented, after which dozens of community members, students, teachers, and parents weighed in on the issue. The meeting ended before all the public comments could be voiced. Video of that board meeting can be found here.

“There are a lot of parents that are concerned about this issue,” Nori said. “It’s complicated, right? I think everyone has good intentions, and we all want what’s best for our children.”

One reason that detracking is such an important issue is that it’s highly contentious. Around the country, wherever detracking has been implemented, controversy has followed. In San Francisco, for example, a 2014 policy preventing students from taking Algebra I until 9th grade has been a constant topic of concern within the city, leading to countless op-eds, a parent organization, and a petition to “Restore Algebra by 8th Grade as an Option” that garnered over 1100 signatures. Detracking with SUHSD has even attracted the attention of national newspapers such as the Wall Street Journal. Additionally, the group behind the Instagram account “SUHSD Students First” has arisen to argue against detracking. The group created a petition that has been signed by over 1100 people. There have not been public reactions of that intensity in support of detracking.

Advocates for detracking provide several reasons in support of removing advanced classes. For one, advanced classes tend to be skewed toward certain demographics. For example, at Woodside, in the 2021–2022 school year, 67% of students in AS English I were white, despite the fact that the school was only 43% white in the same year. Detracking can help ameliorate such a demographic divide so that the classes more closely resemble the demographic makeup of the broader student population.

Supporters of detracking have also observed that different middle schools cover different material in eighth grade. In an interview she gave to The Paw Print last year, former Woodside English teacher Kathleen Coughlin observed that differences in knowledge holds some students back and that a detracked English class gives all students a unified base on which to proceed.

“Some students have studied irony, some students have studied more complex forms of characterization, and some have not,” Coughlin said.

Lastly, proponents of detracking voice the fact that certain measures of academic success have occurred as a result of detracking. At Sequoia High School, for example, detracking led to a substantial increase in enrollment in their advanced 10th grade “English II ICAP” course, so much so that according to the draft report, “barely any students enrolled in [regular] English II.” Furthermore, after Woodside detracked their freshman English offerings, pass rates for high-achieving students—students who would have taken AS English I before it was removed—stayed roughly the same, and socioeconomically disadvantaged students “increased their likelihood of meeting the ‘B’ requirement necessary for admission to the UC/CSU system.”

On the other side of the debate, critics provide several reasons that detracking is not a good idea. For one, while a lot of data has been collected about pass rates, matriculation rates, and 11th- and 12th-grade standardized test results (on which detracking has had little effect) , there is not yet available standardized testing data from 10th grade that would provide a true assessment of learning outcomes. All we have is data about pass rates and matriculation, which doesn’t actually allow for an analysis of how much students learn before and after detracking occurs.

Critics also take issue with the application of the principle of “equity,” a term that loosely means “fair and equal treatment.” While eliminating advanced classes may increase minority and socioeconomically disadvantaged student enrollment, many argue that doing so deprives advanced students of a chance to challenge themselves. Some have even argued that detracking sends a wrong message of low expectations to students by presenting an ‘easier’ option for all students when instead students should be given high expectations.

“I think the question is, what can we do to raise the bar for all students?” Nori stated. “I’m just not convinced that [detracking] is actually raising the bar.”

Lastly, opponents of detracking argue that depriving advanced students of an environment where they can be surrounded by peers of approximately equal academic proficiency is unjust. Studies show that when students are surrounded by peers of equal or greater academic proficiency, they do better, not to mention the fact that most advanced students prefer environments where they are surrounded by similarly advanced classmates.

That was not an exhaustive account of the pros and cons of detracking, of course, but merely a brief summary of some of the important arguments for and against it. As of now, November 14, there have not been any publicly announced plans for further detracking in the district. On November 15, the SUHSD is set to vote on detracking.

“We are a very positive community that cares deeply about education,” Nori said. “I think that’s reflected in how strongly people feel.”

This story was edited on November 28, 2023 in order to eliminate accidentally-biased language.