A federal judge re-enfranchised more than 3,000 Georgians on November 1, just five days away from the 2018 midterm elections.

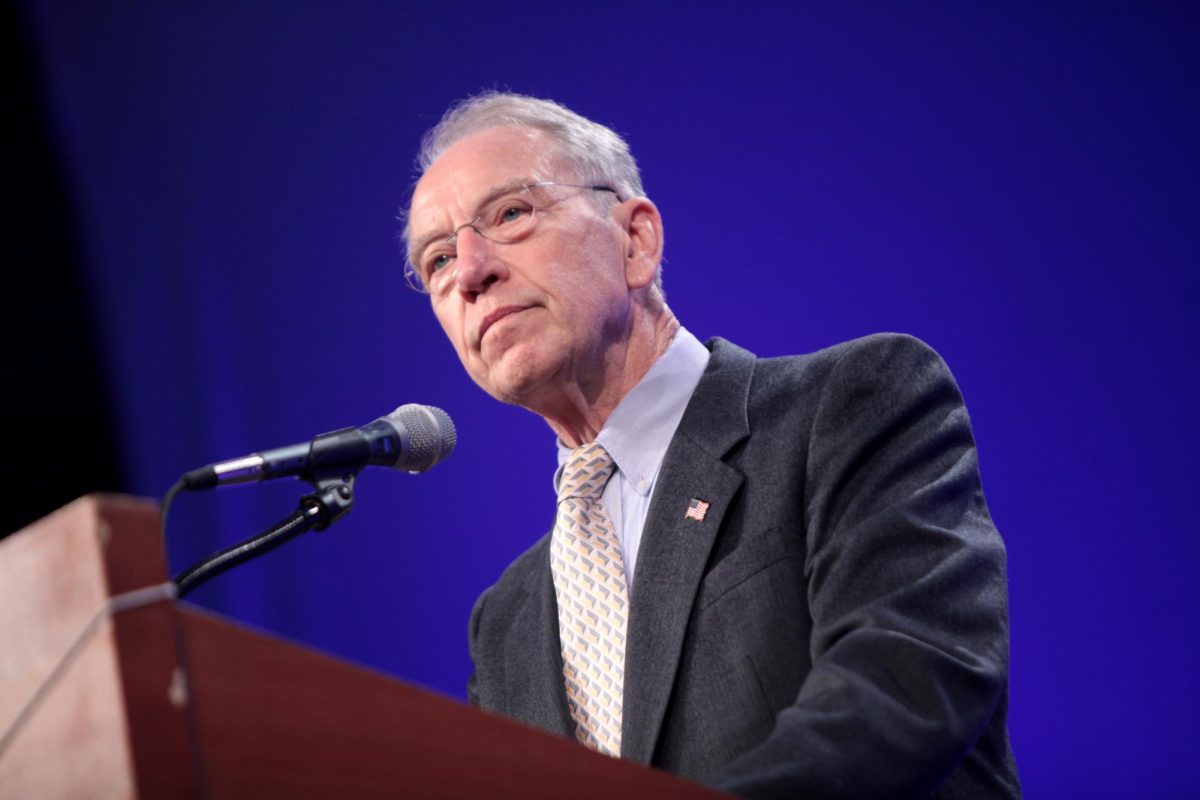

This ruling was part of a class-action lawsuit on behalf of more than 50,000 Georgians who had been purged from the state’s voter rolls. Georgia’s governor race is tightly contested between Georgia Secretary of State Brian Kemp, a Republican, and Georgia Representative Stacey Abrams, a Democrat.

Georgians who had registered to vote in the past but may not have voted in recent elections have found themselves off the voter rolls thanks to Georgia’s “use it or lose it” rule, which purged registered voters who did not vote. Kemp, one of the candidates for governor, is personally overseeing this controversial policy and the electoral process in Georgia, leading many to cry foul.

The question remains: is there such low turnout in U.S. elections? Michelle Bukowski, a Woodside government teacher, has answers. “Well, the official answer is voter apathy, and people don’t see why it’s important to vote,” Buckowski explained. “However, there are some really intentional reasons why it’s not easy to vote. Election Day could be a Saturday, or a holiday to make it easier. It’s easier to shift the blame onto apathetic voters than to make it easier to vote.”

Tactics to suppress voter turnout and disenfranchise have popped up all over the country. For example, North Dakota’s tight Senate race between incumbent Heidi Heitkamp and Republican challenger Kevin Cramer was thrown a curveball last month when the state passed legislation requiring a residential address on acceptable voter identification. Most Native American voters in North Dakota don’t have residential addresses, and previously, only a P.O. box was necessary. In a state where the Democrat only won by less than 3,000 votes and Native voters went overwhelmingly for Heitkamp, many believe laws like these have one purpose: suppress the vote.

Now, interest groups and Americans in those states must go through the court system to challenge new voting restrictions, and in many cases, the courts don’t rule in favor of the voters. North Dakota’s new ID requirements were challenged at the Supreme Court, with the Supreme Court siding with the state of North Dakota, effectively disenfranchising thousands of Native American voters.

Brian Scott, a canvassing volunteer in Modesto, California, explained: “If someone doesn’t know where their polling place is, or what their rights are, their voice could be silenced.”

This election day, the country will see the effect of voter ID laws, “use it or lose it” rules, and other ways states have tried to get fewer people to vote. Many of these laws were allowed after the Supreme Court rolled back key aspects of the Voting Rights Act in 2013 in Shelby County v. Holder; previously, areas that have had a history of voting discrimination needed federal supervision and approval before implementing new rules on voting.

Some Woodside students are prepared for voting and civic engagement. Forty percent of students 16 and over said that they were pre-registered to vote. Senior Victor Saliba said that being pre-registered is important “because it saves you the hassle of having to register the day of.”

Once the results of Tuesday’s Midterm elections are in, the full extent of voter suppression tactics will be seen. Whether Democrats or Republicans win the House or Senate, thousands of voters in many states won’t be able to cast a ballot, whether because of voter purges or new rules designed to silence voters of color, like the Native American population in North Dakota.

Buckowski reiterated the gravitas of voting: “It’s the most important thing we can do, and the most brilliant thing the powers that be have done is convince people that their vote doesn’t matter. It does.”